Something must give in Wyoming’s Tetons. An interagency working group has proposed that some prime backcountry ski terrain in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) and surrounding National Forests be off-limits to seasonal winter use to protect high-value bighorn sheep habitat.

At issue are an endemic herd of Teton sheep and their disturbed winter range. The herds, split between north and south sub-groups, number approximately 100-125 individuals in total and are at risk of local extinction. The Teton sheep were once migratory, but as those traditional migratory routes were disturbed, they became year-round Teton residents.

A 2014 masters’ thesis (Courtemanch 2014) showed backcountry skiers stress sheep causing them to move off their preferred habitat. The disturbance isn’t willy-nilly habitat destruction but subtle sheep-human interactions. We may think of ourselves as silent sport participants, which in most instances we are, but silent sport, in this context, may be too loud and intrusive for Teton sheep.

“Individual bighorn sheep exposed to high levels of recreation exhibited increased daily movement rates and home range sizes compared to sheep exposed to low or no recreation. These results reveal that bighorn sheep appear to be sensitive to forms of recreation which people largely perceive as having minimal impact to wildlife, such as backcountry skiing,” reads Courtemanch’s thesis on pages 1-2.

The sheep’s “avoidance behavior” adds stress, which in winter can unduly compromise an animal’s health. The working group has also cited other factors adversely impacting the sheep like climate change, and disease transmission from mountain goats.

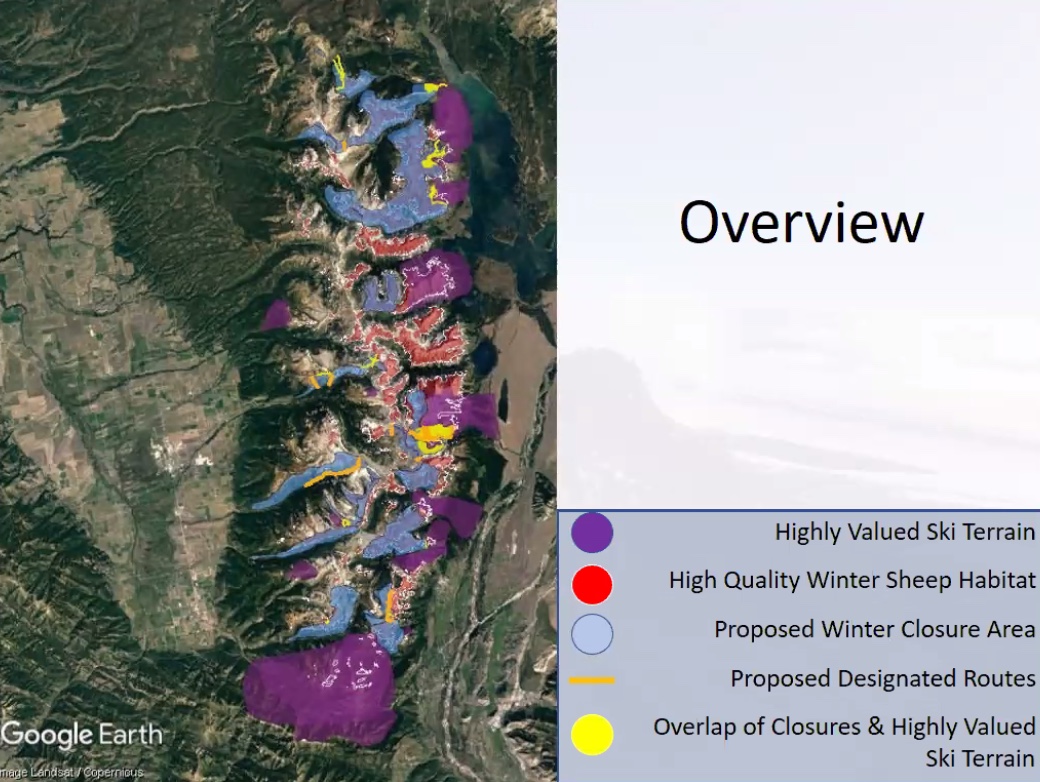

An broad overview of the proposed impacted areas in the Tetons. Screen capture image from Teton Working Group presentation.

The Working Group

Courtemanch, the author of that 2014 thesis, has since gone on to work for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. According to tetonsheep.org, Courtemanch and five others constitute the Teton Sheep Working Group, a multiagency group tasked with engaging stakeholders, deriving possible solutions, and recommending a final action. The working group includes three wildlife biologists, a research associate from the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, the now former Executive Director of the Wyoming Sheep Foundation, and a biological science technician from the local National Forest.

(The Wyoming Sheep Foundation aims to protect existing sheep populations. The Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, which first received non-profit status in 1987, appears to do valuable work. Their website, however, does not include any information beyond a physical address. It’s 990, a disclosure form for non-profits lists $636,765 in net assets/fund balances for the end of year 2019.)

No representative from the local recreation community serves on the working group – which may be the norm for such groups deciding on wildlife management issues. The working group, by most accounts, did engage local stakeholders, including the backcountry ski community, in a bottom-up approach to information gathering and consultation.

Wednesday evening, the final of several public forums between stakeholders and the working group was held remotely.

Jeff Dobronyi, a Teton based IFMGA guide, raised several questions about the proposed closures at the meeting. Specifically, he asked the working group to consult skiers to determine the ground level closure boundaries.

“On the satellite image overviews, the closures looked like large rounded polygons with little specificity regarding areas of deep snow and areas of shallow snow, which we know affect sheep movement patterns and little specificity beyond the drainage scale,” he said. “Would you consider adding a few backcountry skiers to the working group to help narrow down the closed terrain on a slope scale?”

The forum’s moderator answered before Dobronyi had finished. “Oh, yeah, I think that will happen, Jeff,” she affirmed.

Potential Closures

(A full menu of images detailing the closure areas is available in the working group’s full recommendations.)

But again, something has to give. And for now, it appears that some desirable ski terrain in GTNP and surrounding National Forests will be restricted. According to the working group’s recommendations, 68 actions, ranging from high to moderate and low priority, were considered, and they also explored the feasibility of implementing the recommendations.

In total, skiers identified 57,266 acres of what they call “high-value” terrain in the Tetons. Courtemanch’s research identified 45,278 acres of “high quality” sheep habitat in the region, including areas outside the Park. Needless to say, if we overlaid those areas, there would be some overlap.

But ground zero for skiers is the Park. The working group identified 36,068 acres of high-quality sheep habitat there, of which only 4% is currently closed off to humans. Skiers highlighted 28,268 acres of GNTP as high-value ski terrain.

If the high and moderate priority actions are adopted, 47% of the Park’s best sheep habitat will be off-limits to humans in winter. Nine percent of the identified high valued ski terrain will be off-limits if all actions are approved.

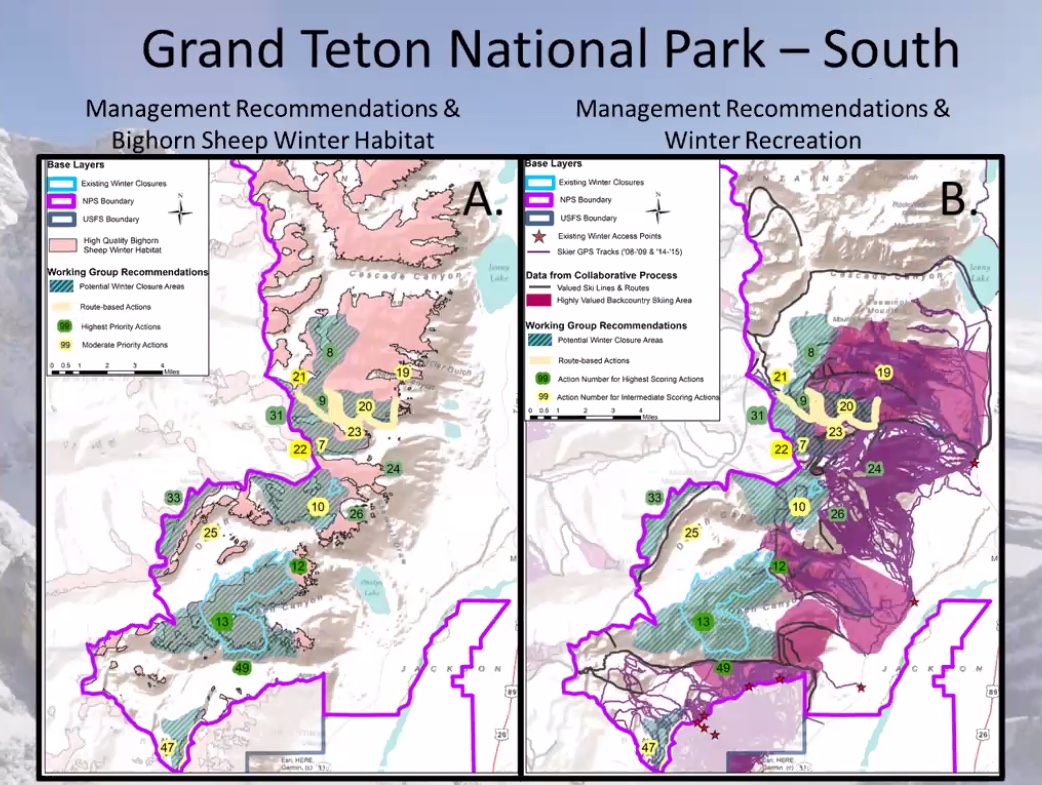

The ski terrain left open includes options in Granite and Garnett Canyons, Mt Moran, and the east faces rising above Jackson lake.

However, they also recommend some closures in the North Fork of Avalanche Canyon and portions of Rendezvous Peak, which sits just south of the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort on land managed by the Forest Service. (This is not an exhaustive list of potential closures.)

In some cases, the working group also recommends short and narrow paths so skiers can pass through off-limit zones and connect open zones.

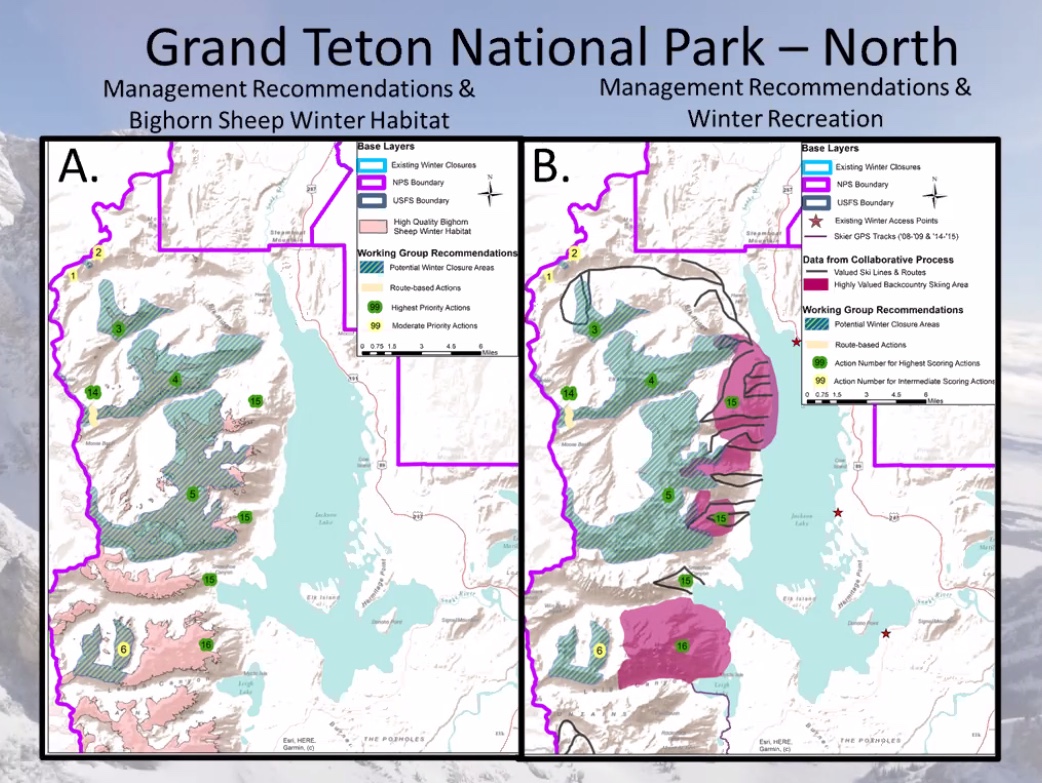

A slide from the working group showing an overview of closures and high value ski terrain in the northern portion of GTNP.

A slide from the working group showing an overview of closures and high value ski terrain in the southern portion of GTNP.

Wednesday’s Final Meeting

With closures looking likely, Eric Hawes, a skier commented, “Looking at permanent closures and what seems like an indefinite period of time, we’d just like to see what the end state would be for these permanent closures. You mentioned metrics of success: 100 sheep per herd. What actions would then be taken?”

At this point, the working group was non-committal in defining a discrete time frame to determine success or failure and when, if at all, or under what circumstances, they might rescind closures.

That has been a point of contention for some skiers: they want to know the potential long-term duration of the closures and what defines success or failure for a viable sheep herd explicitly.

Unsatisfied, Jay Hause, another skier, pursued an answer by asking, “If the closure is proven ineffectual, what is the time frame to reopen the terrain?”

Sarah Dewey, a Park Service wildlife biologist from GTNP responded, “So I think, Jay, that we will continue to monitor and see what bighorn sheep use is. And based on that, we will adapt. But if the closures are effective, they may be kept in place for a long time.”

Hause pushed again, “Is there any outcome where the closures go away? It seems like the closure is like a one-way ticket. And it just leads to more closures.”

At this point, Courtemanche, who was contacted for this story but was unavailable for comment, jumped in. She was often the point person, answering questions on behalf of the working group and offering substantive answers.

“I think that’s a great point, Jay, and I would say, there’s a lot of closures that have been put into place at various times in the past few decades, that honestly, haven’t had much follow up monitoring or, you know, reevaluation of if they’re still needed, or, you know, could they be tweaked,” Courtemanche responded. “I’m not necessarily talking about the Tetons, but just kind of everywhere. I think that’s something that is really great for the working group to hear from you guys. And I feel like that’s something that we do all the time with wildlife management is, you know, whether it’s every three years or five years or whatever, go back and look at is this working? Do we need to change anything?”

Courtemanche continued, “Personally, I’m not speaking for the agencies, but personally, I feel like that would be a totally fair thing to work into this process of saying, you know, okay, X number of years down the road, we’re going to take another look and kind of see if there are changes needed.”

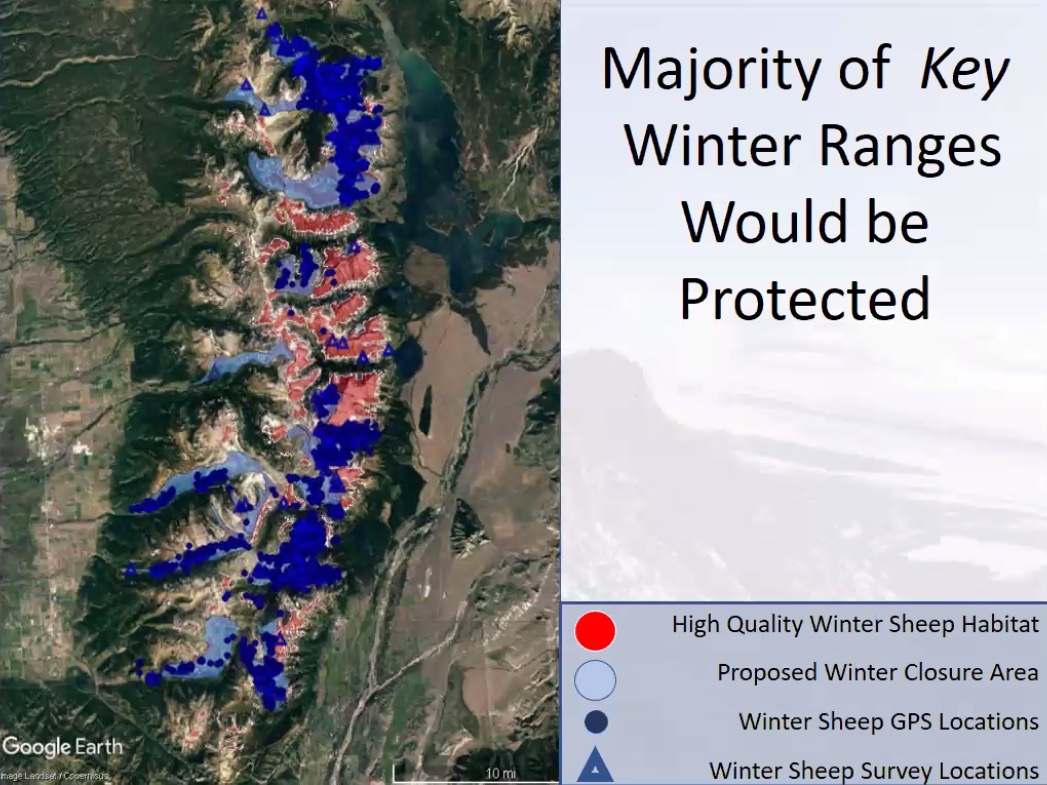

A slide from the working group’s Wednesday presentation showing that the majority of winter range for the sheep would be protected.

This messy and imperfect process moves forward. There is much to consider. Jackson Hole and the surrounding mountains are complex. It stands as both wilderness and a bustling tourist mecca with a major airport within the confines of GTNP. There is a new permit for potentially disruptive helicopter tours in the Park and pressure to expand pre-existing ski resorts on both sides of the Teton divide.

Zahan Billimoria, another IFMGA guide who attended Wednesday’s forum, has been thinking about potential actions and where it fits into his world view as a parent, skier, and longtime community member.

“Humans are wilderness, that is our habitat in the same way it is habitat for animals,” he said on a call on Tuesday. “That’s not a platitude, that is actually how our species has evolved. We are hardwired in the same way that animals are as biological organisms, who interpret their environment and create adaptations accordingly.

“Due to our connection to nature, and that applies to so many aspects of our life, from our ability to have empathy for living creatures, including ourselves, to live pain-free and move efficiently, to be creative; all of these innate human capacities, are what our species has derived and figured out as a result of living in our natural habitat. And of course, in the last 100 years, we have never before in all of human history ever lived so far, or separate, from the conditions that nature provides.”

Billimoria’s thoughts resonate with those seeking solitude and a physical and mental test in the mountains. This might seem cliché, but it is a truism repeated over and over. It goes something like this: “I feel most alive when in the mountains.” We know what this means as skiers — Billimoria’s logic hits home.

The challenge, it appears, is that others receive that same sense of awe in the presence of wildlife, sheep in this case. Several people stated as much during Wednesday’s meeting.

Chip Jenkins, the Superintendent of Grand Teton National Park, addressed skiers directly as he said Park administrators would be looking “strongly at the recommendations for closures.”

According to Courtemanch’s 2014 thesis (page 88), limiting winter recreationists in and adjacent to suitable winter sheep habitats was vital for their survival. Nearly eight years later, with the Teton herd still compromised, winter recreationists are backcountry skiers.

Jenkins’ made clear the Park’s legal mandate to protect wildlife. He also appealed to the ski community to be stewards of the Teton sheep.

“Now’s our time,” said Jenkins in his closing remarks. “We know that some people have made choices about how to live your lives, to feed your soul, with the ability to enjoy and experience tremendous wilderness experience and backcountry there. We also know that there are pressures and threats to bighorn sheep from disease and competition for habitat. And the decisions and choices that we all make will create a legacy that we’re going to hand down to the next generation. It’s the choices that we’re now faced with.”

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.