More than one person, or group, in a backcountry setting means communication can get complex.

You’ve headed into the backcountry with your core group of partners. The day’s avalanche forecast informs you. The communication is good; checking egos, you discuss skin track and descent options. After several thousand feet of climbing, you see a few fresh tracks snaking into a couloir at the drop-in point.

It appears some other group has a similar ski objective.

A basic thought experiment about how a common radio channel might benefit skiers in this situation has some essential upsides – first and foremost, knowing if a party is skinning adjacent terrain below or if you are about to ski on top of another group.

The idea of group to group communication in the backcountry is not new. Group to group communication, in this context, is communication between two discrete ski parties on a shared or known radio channel. After a season in Telluride, back in 2016, Matt Steen and Bruce Edgerly presented findings related to the use of a shared radio channel for skiers from different groups in the Bear Creek drainage. What Steen and Edgerly found was that intentional communication between groups could potentially reduce hazardous situations from arising.

“Introducing advanced communication through the use of radios, and specifically a common radio channel in high-use avalanche prone areas, is a way to aid in efficient avalanche prevention, safety and rescue. Use of radios increases the orderliness of communication among group members, between groups, and between groups and safety professionals in high-use backcountry terrain,” Steen and Edgerly concluded.

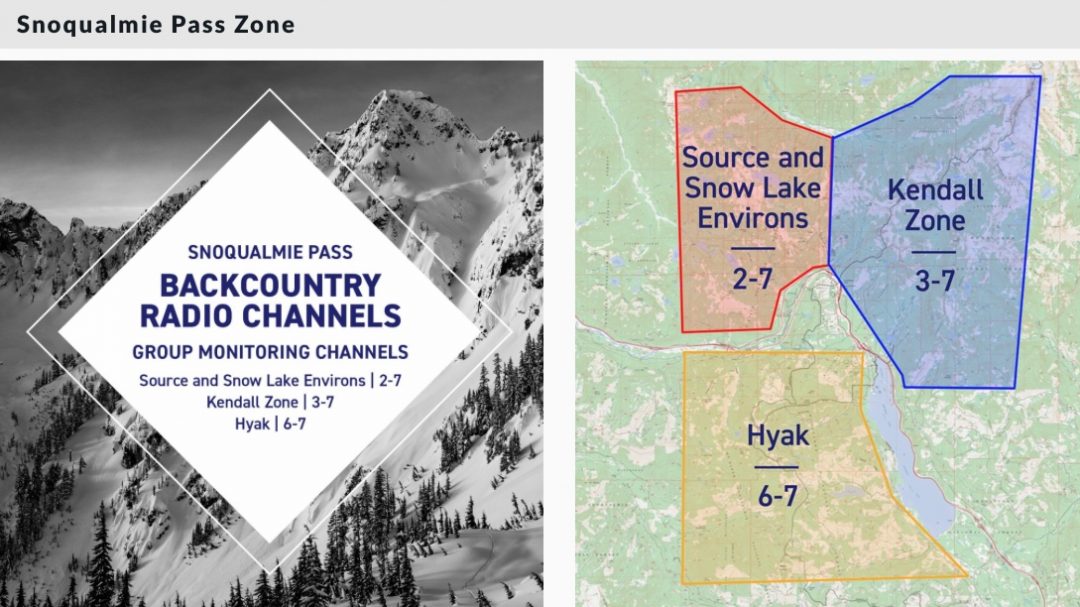

Last night, on the Northwest Avalanche Center’s virtual NSAW (Northwest Snow & Avalanche Workshop), Justin Davis, a member of SPART (Ski Patrol Rescue Team), a unit of King County Search and Rescue, presented information about a common radio channel initiative. The program encourages backcountry travelers to use a common radio channel in three distinct zones off Snoqualmie pass.

(Disclaimer: this is not an official NWAC program: “This program is NOT designed, managed, or monitored by the Northwest Avalanche Center forecasters and staff,” states the NWAC website.)

The Snoqualmie Pass Zone and related radio channels.

The gist of the program seems practical and straightforward. Users enter complex terrain, and when they enter that terrain, they know to switch their radios to a specific channel and code. (The three Snoqualamie zones each have a unique channel/code – see map above.)

A radio set to the appropriate channel/code allows a skier to monitor and communicate with other groups in that zone. During the presentation, Davis played audio from a day when several parties were skiing avalanche-prone terrain, and the inter-group communication was compelling. Users kept their discussions brief and precise, with essential information relayed like position and intent.

The program lays out the following uses and protocols:

Communication between multiple groups:

- When your group is about to enter complex terrain

- Information regarding potential hazards or critical snow & avalanche information

- When your group is clear of a given line or area, alerting other groups of a clear run-out zone

Other uses:

- Send a distress call for assistance in case of an accident

Request another group to call 911 or mount an organized rescue if 911 can’t be reached directly - Communication between partners as they travel in complex terrain (example, between zones of relative safety)

Regardless of the time and place, we know that agreed-upon norms for group to group communication are imperative. This small-scale project off Snoqualmie Pass might make us all safer out there.

Editor’s Note: Linked here is information about a similar program on the UAC website. This initiative involves the use of common radio channels in Little and Big Cottonwood Canyons and the Park City Ridgeline.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.