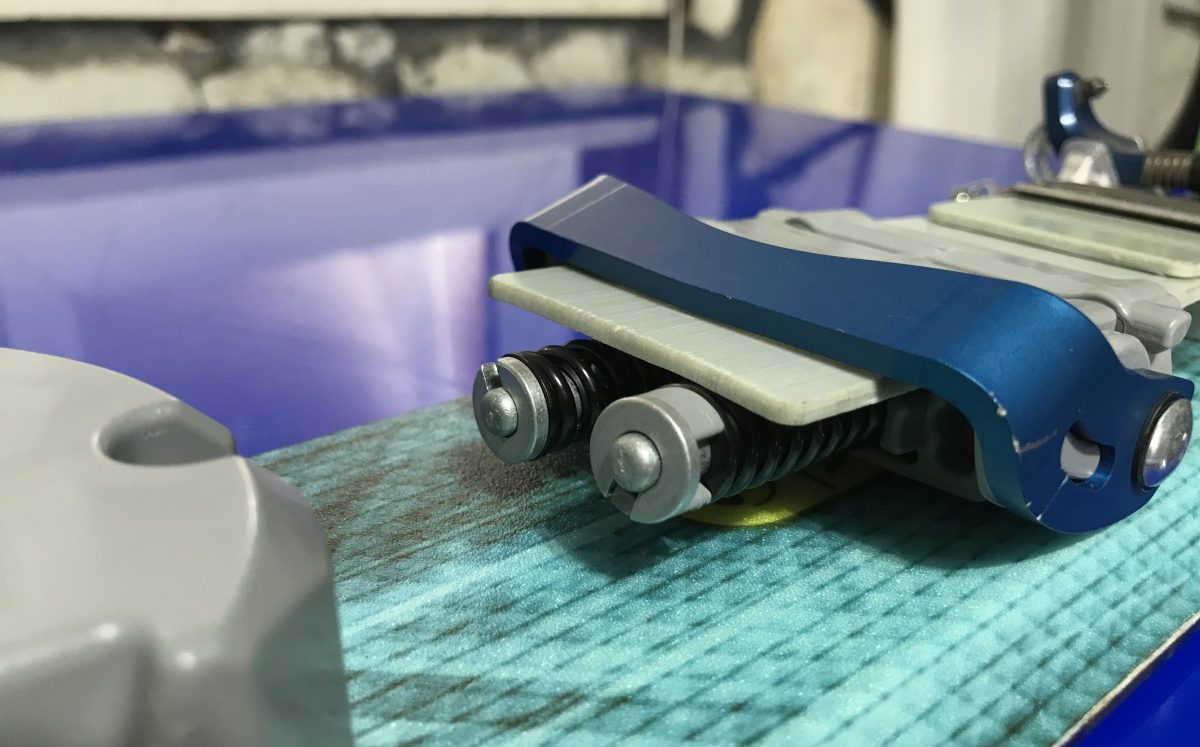

The 22 Design Lynx binding, paired with Voile’s HyperVector BC (ski strap there to hold skis together).

The Canadian Lynx is perhaps North America’s closest counterpart to the snow leopard; a sizable feline predator particularly adapted to snow-bound environments. Near the turn of this century, the Canadian Lynx was re-introduced to Colorado in an attempt to re-establish the range of this agile snow-focused predator following extirpation by hunting, trapping, and poisoning.

The introduction of the Lynx binding by 22 Designs is something of a parallel effort to make tele skiing a more viable option after nearly being killed off by the tech binding. This North American designed, and manufactured binding represents one of the most significant leaps forward in tele bindings since NTN progressed tele bindings beyond its birch shoot roots.

The Lynx binding takes advantage of the tech toe design that was part of near death knell for tele bindings. As it turns out, it’s not enough to free just the heel as the old guard of telemarking exhorted; a free pivoting toe is crucial for maximum uphill efficiency. Prior to the pin tech toe being adapted, the “free pivot” provided by tele bindings such the Voile Switchback, and BD 01 (my previous “Tele Touring” binding) still relied on having the binding attached to the boot in tour mode, and placed the pivot point forward of the toe. Pin tech tele bindings provide the opportunity to position the pivot point significantly closer to the toe, while freeing the boot from the trappings of the binding when in tour mode. The design advantages of moving the pivot point closer to the toe are similar to “short stroking” an engine to allow for quicker revolutions, and the advantages in weight reduction are obvious to anyone who has ever stepped out of hiking boots into flip flops.

While the tech toe was an adaptation of an existing design, the composite leaf springs are a great example of “old” ideas being executed in a novel way. According to Chris Valiante at 22D, the leaf springs allow for lighter weight, while also permitting the coil springs that lock the 2nd heel into place to be smaller as well. In addition the leaf springs allow for quicker engagement as soon as the heel is lifted.

These advantages place the binding in comparable weight range to hybrid style tech bindings such as the Marker Kingpin, or Salomon Shift. Coil springs, and U-springs are both more “advanced” forms of springs, but in this case, incorporating the more “modern” composite material instead of the long-running standard of metal springs allowed the older technology of leaf springs to be a better solution.

The “Claw” element of the 2nd heel / NTN attachment relies on a pointed cam mechanism working against the tension of the coil springs to lock the “Claw” into the open / touring position. In this mode, only the tech toe engages the boot, same as a classic alpine touring setup.

With the cam rotated down, and disengaged, the coil springs cause the Claw to latch onto the 2nd heel of the boot for ski mode. The tension of the coil spring against the claw keeps the boot attached to the binding; the leaf springs provide the “activity” of the binding.

Changing the preload pin is not recommended as an “in the field” operation. A sampling of the tools used in attempting to depress the spring-loaded latch on the lock pin. The bent pin flag proved to be the most effective instrument.

Other users have commented on the composite plates splintering at the edges, but so far that has not been an issue for my set.

They are remarkably quiet, in contrast to various random squeaks and squeals that other tele bindings I have skied with (G3 Targa, and Riva, BD 02) have exhibited.

A comparison in pivot points of the tele gear owned by the author.

Back: The 22D Lynx / Scarpa TX Pro combo has the greatest mechanical advantage by placing the pivot point closest to to the toe in both stack and reach.

Middle: The BD02 / Crispi CXP combo has pivot point perched significantly higher than either the tech binding, or the 3 pin binding, and the most weight attached to the boot in tour mode.

Front: The classic G3 Riva / Alpina leather boot combo wins for light weight and comfort (not to mention you can drive to the trailhead in them!), keeps the pivot point just as low as the tech boot / binding combo, but places the pivot significantly farther back, nearer to the ball of the foot rather than the tip of the toe. This can help by applying constant pressure to the climbing scales for more consistent traction, but makes breaking trail much more of a chore.

Evaluating the performance gains of the tech toe design immediately bumps up against the limitations of tech-compatible tele boots. Though the tech toe is all about maximizing uphill performance, all current tech-compatible tele boots have been designed with downhill performance as the primary goal, and uphilling a vague afterthought. While I did appreciate the free-pivoting toe, the limitations of the Scarpa TX Pro boot is significant enough that I can’t say it was a distinct improvement over my Crispi / BD 02 combo in the way that switching from frame bindings to tech bindings was.

While the gains in uphill performance are sadly negated by the lack of progress in tele boots, there is a distinct advantage to be found on the downhill by the increased control of the tech toe / NTN 2nd heel combo. Much of my prior experience in tele skiing has been marked by the vague sensation of “is it working yet?” when initiating turns, followed by a distinct limit of “now you are just bending your knee for no reason.” The Lynx bindings have a very progressive feel; marked by instant engagement on turn initiation, and a well-modulated increase of power the deeper you bend into the turn.

The author in the final moments of bravado on a resort day, before panicking at the thought of hitting the photographer (Justin Vaughn)

Following a recent storm, I curbed my normal impulse to grab the Mega Meadow Skipper, and went with the Low-Angle Dangle Wrangler. I had read numerous comments of the binding being prone to locking up in powder touring conditions, and felt it my duty as Wild Snow tester to verify.

Barely out of sight of my truck, and breaking trail in boot-deep snow, the Claw locked onto my boot. I turned for a wistful look back, regretting not bringing my AT gear for back up. Shouldering the weighty burden of quasi-scientific testing purposes, I forged ahead, one heavy step at a time. The locking issue was persistent for the entire tour, engaging the Claw every few hundred meters or so. Fortunately, this coincided with my need to stop and catch my breath, so the malfunction wasn’t quite as frustrating as it could have been. After a few cycles of involuntary engagement, I began to detect the distinct “click” of the Claw popping up, and could push it back down with the tip of my ski pole before it engaged the boot.

Every binding I have ever skied on, be it frame, tech, or tele has had some degree of snow buildup / icing. The “false riser” of snow that builds up my Dynafit bindings in similar conditions is equally annoying in low-angle conditions for the fact that the resolution is far more tedious. One must bend down to rotate the tower to clear the compacted snow, then brush excess snow aside to enjoy wedge-free touring for a few strides. At least the Lynx binding can easily be tapped down with the tip of a ski pole, without requiring any vexing bodily contortions.

Reaching out to Chris Valiante at 22D, he suggested adding more power spacers to combat the issue of the 2nd heel locking in powder conditions. Currently, I have been running my setup with no power spacers.

Chris Valiente at 22 Designs suggested adding a power spacer to combat the issue of the Claw locking into ski mode while touring in fresh snow. One power spacer was enough to significantly change the amount of force required to switch the Claw from one position to the other, enough so to compromise the ease of pushing it down with a ski pole, but hopefully enough to mitigate unwanted locking of the binding.

The bright side to the conundrum of the auto-engaging claw is how readily the binding switches between tour, and ski mode. Skiing performance aside, this is one of my favorite features of the Lynx binding. It is far more convenient than the tower rotation most tech bindings depend on, and requires less force to switch between modes than the BD 02 that was my previous tele touring setup. The BD / Cable design has its own icing issues, either building up under the boot, and creating an uncomfortable wedge, or requiring stepping out of the binding to clear ice from the ski / walk mechanism.

It’s a fairly minor nitpick, but the basic two-wire design of the heel riser feels a bit out of step with the precision of the rest of the binding. While I can admire the classic, functional element of the wire bail riser design, it feels like slamming the doors shut on a squarebody Suburban v. the light, precise “snick” of Dynafit risers clicking into place, which feels more like closing the door on a Mercedes S-Class.

The Lynx binding, like its feline namesake, is well adapted to winter travel (minus the icing issue). Will its introduction be enough to bring telemark back from the brink of extinction? As with any re-introduced species, a variety of environmental factors determine the chances of success. In the case of the binding, the introduction of touring-friendly tele boots with tech fittings will be the most significant variable in whether tele touring remains on the Endangered Species list, or is able to rebound to its former populous numbers.

Wary of a fellow apex predator, the Lesser Long-Tailed Colorado Lynx approaches with caution. Note the powerful pinchers of the 22 Designs Lynx poised to strike at any tech fitting toe that might wander nearby.

Aaron Mattix grew up in Kansas and wrote a report on snowboarding in seventh grade. His first time to attempt snowboarding was in 2012, and soon switched over to skis for backcountry exploration near his home in Rifle, CO. From snow covered alleys to steeps and low angle meadows, he loves it all. In the summer, he owns and operates Gumption Trail Works, building mountain bike singletrack and the occasional sweet jump.