Tracee Metcalfe negotiates a knife ridge on Ama Dablam. Photo: Kevin Kayl

Dr. Tracee Metcalfe is a physician located in Vail, Colorado. For the past eight years, she has spent March and April finalizing training and traveling to work as a high mountain doctor in Alaska and the Himalaya. She has volunteered as medical personnel on Denali, worked as a base camp doctor on Manaslu, and served as climbing doctor on Makalu, Everest, and Cho Oyu, all of which she has also summited.

This spring instead of wrestling with big mountain environments, she battled the new coronavirus — both personally and professionally. I caught up with her in late April to talk about high mountain medicine, having a case of COVID-19, and treating others.

GS: What is your line of medicine?

TM: I’m an Adult Hospitalist at Vail Health Hospital, which is an internal medicine doctor, I manage non-surgical patients that require admission to our hospital either from the ER or from their doctor’s office. Heart attacks, infections, problems with altitude, etc. About forty percent of the time, I co-manage orthopedic patients which means I manage their chronic medical issues so their surgeon can focus on the operation.

GS: Explain how that role shifts when you are on the mountain.

TM: The big difference between Expeditions Medicine vs. Hospital Medicine is the lack of resources available — both tests and medicines. The first questions on my mind with each patient are: how sick are they and do I need to plan an evacuation? I see coughs and shortness of breath and then try to figure out if it is altitude-related disease such as High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) versus a cold or pneumonia. One symptom I see both at the hospital and on the mountain is chest pain. It is much easier to rule out life-threatening chest pain in the hospital since you have EKG and X-Ray at your fingertips.

GS: You’re a skier. Have you ever skied on the big mountains you’ve worked on?

TM: I would really like to but I have not. Working as a doctor, I asked several times to bring my skis. Not to try and ski off the summit — that doesn’t really fit with your job when you are keeping people safe — but to ski around base camp. I was always told no, too much extra gear, etc. On Denali with the climbing rangers, we skied from around 16,000, which is as high as the park service lets you as a ranger.

GS: What was a memorable ski day from this season?

TM: I went to do the Shedhorn skimo race in Big Sky, Montana and didn’t get to race because my boot broke. The next day we got to ski the Big Couloir on a powder day, and were the last ones to ski it for the season due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The ski patroller at the check in was freaking out with all the people that were in there, and she didn’t have any hand sanitizer. I had a little bottle and gave it to her. Her boss called and said to shut it down, but she said “Nope, we have these two girls that need to get through it.” It felt special to get to do that since you could tell things were about to change.

GS: That brings us to the time of COVID-19. You ended up contracting the virus?

TM: When I got back from Montana I started to get symptoms. I had a lot of sneezing, a weird headache, and diarrhea. I was scheduled to go back to work and knew I had been exposed, so I was tested and it was positive. My symptoms were pretty mild other than a headache and runny nose the first few days and I felt like I had kicked it. It wasn’t until 7-14 days later that I started to get a lot more shortness of breath. It was nothing compared to other’s, but I’d been training hard for Nepal yet was getting totally winded just going up and down stairs. I never got super sick, but was definitely fooled at first. It ended up lingering for about three weeks.

GS: You’re back to work now. What’s the scene inside the Vail Health hospital?

TM: We had a fair amount of COVID cases a lot sooner than Denver or anywhere else. We recognized our first hospitalized case in the second week of March. During the next two weeks, we realized that it was already widespread here. We had between three to five new cases per day for a couple of weeks and we had about five to ten hospitalized patients at a given time, which was a lot for us. In the last ten days, we’ve seen a huge drop-off. I think we have one COVID patient in the hospital currently. Shutting the ski area down and the shelter in place order helped.

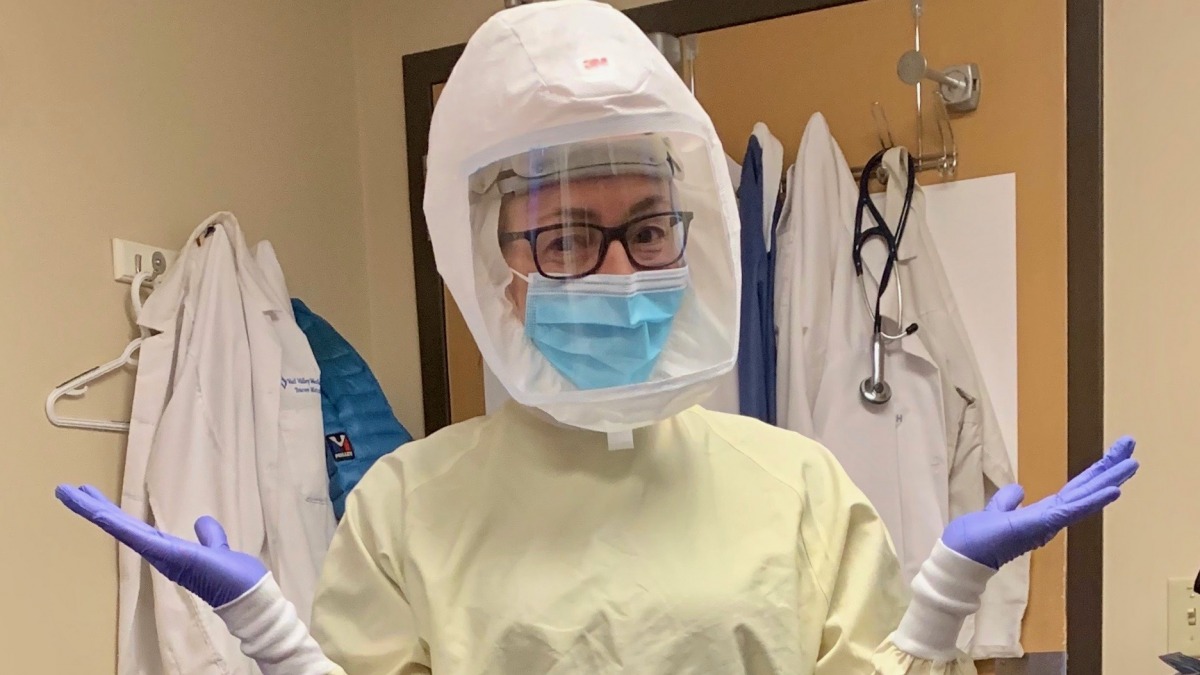

Dr. Metcalfe in full PPE treating COVID-19 in Vail, CO

GS: What was your take at the peak, and now, about people skiing in the backcountry?

TM: Mental health is really important and we see a lot of suicide and substance abuse in Eagle County. I don’t agree with not letting people go outside and ski or hike or do something for their mental health. Do I think people should be getting on super rad gnarly lines? I think that’s a personal decision. I knew I would be a better doctor if I got outside safely and skied, and so I did. Do I want to do anything that’s really dangerous? No. I don’t agree with shaming people though, and it really upset me to see that. I think that some of the people that are doing the shaming don’t know the other person’s skillset. What may be a really dangerous choice for you, may not be for another person.

GS: Was that view shared by others in the medical community?

TM: I believe so. Everyone I talked to at work, when it was very busy, was getting out and exercising or skiing. During that initial surge we were appreciative that people weren’t doing things to hurt themselves. That first week we were totally overwhelmed, paramedics were working their asses off transferring several critically ill patients a day to Denver.

GS: A New York City physician, Dr Cameron Kyle-Sidell, has likened COVID to HAPE, suggesting the acute respiratory distress treatments like a ventilator are wrong for many patients. What is your opinion, being a high altitude doctor?

TM: One thing that is similar is that some people with HAPE will have incredibly low oxygen levels and yet they are still talking and functioning. We’re seeing that same thing with COVID where people come in with oxygen saturation lower than 50% which is crazy. Normally, if a person’s oxygen saturation is even below 80%, they’re incredibly short of breath, panicked, and gasping for air. The way that the COVID patients are behaving is similar to HAPE but I participate in a lot of high altitude medicine discussion groups and annual meetings; we think the physiology of what’s happening inside your lungs (with COVID19) is different. The patient looks sort of similar, but at a cellular level, the kind of damage is not the same.

When somebody has HAPE you don’t put them on a ventilator for several reasons, but not because it’s dangerous. First, you can treat with oxygen and descending to lower altitude. Also, there’s no ventilator at 17,000 feet on Denali or 20,000 feet in Nepal. We don’t know if putting someone with HAPE on a ventilator would help or hurt.

GS: Your mountain doctor gig for this spring was cancelled. Will you push until next spring?

TM: Yes I was supposed to leave for Kangchenjunga on April 4th. I love our backyard so I don’t have any plans to go anywhere until next fall at this point. I want to focus on local stuff. I was thinking about climbing the Matterhorn in August, but I don’t know if that’s realistic. I had some aspirations to do some climbing on Mount Cook in New Zealand in November, but I still think next spring will be when it’s time to do an international objective.

Dr. Metcalfe plans to be a little closer to home this year, probably enjoying something like this.

GS: You’ll go for Kangchenjunga next year?

TM: I was really excited about it and have spent a lot of time researching it. It sees the second least number of attempts of any of the Nepali eight thousand meter peaks. It doesn’t see much climbing. It has some pretty technical parts to it so yeah I’m pretty — I don’t want to say obsessed but if not next spring, at some point I want to make that trip happen.

GS: Do you think we’re going to have permanent effects from this pandemic for big mountain missions?

TM: I don’t see things turning to normal with travel and expeditions until we have a vaccine and a lot more testing. I think people will be back to doing big mountain objectives, but not any time soon.

On March 22nd 2021, Gary Smith tragically died in an avalanche outside of Beaver Creek Resort in Colorado. Since 2018, Gary has been a frequent and insightful contributor to WildSnow. From Christmas Eve spent at the Wildsnow Field HQ cabin, to testing gear and sharing his love for steep skiing around the world, he was a pillar of the ski touring community and will be greatly missed.