This post sponsored by our publishing partner Cripple Creek Backcountry

The first storms of the season have arrived here in Colorado, bringing all-too-familiar anticipation for the winter to come. There’s a healthy mix of optimism, superstition, and skepticism about the future of winter in this part of the country (especially after last season’s scarcity). The Colorado Snow and Avalanche Workshop (CSAW) is a great place to bring those perspectives together in one room. I’ve been making an effort to attend the last few years as a way to connect with peers in the avalanche industry, get updated on new research, and to begin tuning my brain back into the avalanche environment after many months away. I have found these one day workshops to be both enlightening, entertaining, and definitely worth the ticket price, which benefits local avalanche centers.

The 17th annual CSAW in Breckenridge was packed with a variety of topics, some more intriguing to me than others. Subjects ranged from: the History and Future of Avalanche Mitigation on Colorado’s highways; new forecasting tools (read: new satellites!); rain on snow forecasting considerations; ski season lengths as effected by climate change; and the ridiculously resilient ridge that plagued the state’s 17/18 winter and what the predictions are for the upcoming winter.

History and Future of CDOT Avalanche Mitigation Program

The highway system in the state of Colorado exposes travelers to a huge amount of avalanche terrain, which is often unnoticed or seemingly benign. The workforce it takes to keep the thousands of highway users safe throughout the snowy months is incredible, and only rivaled by locations such as British Columbia and Alaska (in terms of terrain and mitigation work required). CDOT (Colorado department of transportation) and it’s avalanche mitigation team started as a result of an increase in mining and winter time recreation. More need to keep roadways open year-round for industry and people safe from the avalanche hazard. It’s not surprising this was/is a hot topic as the state’s main Interstate Highway cuts directly across the Rockies and through the continental divide, and not to mention the lesser known highways that travel through some of the country’s most rugged terrain. As user groups continued to grow, mitigation strategies for CDOT changed.

In the 1950’s the howitzer came into use as a way to trigger hazardous path’s start zones. As soon as the 80’s and 90’s the avalauncher had come into play, specifically a McCracken launcher – which had a longer barrel, which equated to longer range and an increase in accuracy. It’s always impressive to think about some of these early highway avalanche workers out in the odd hours in awful weather exposing themselves to the avalanche hazard and shooting WWII era weapons at the mountain. Exciting? Dangerous? Synonymous? Regardless, the risk is real, and there have been a few noteworthy incidents involving highway workers and explosives.

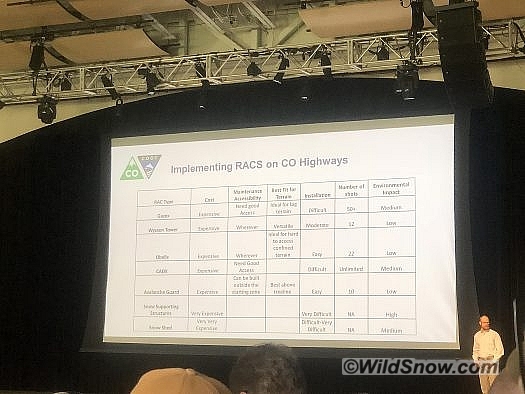

As CDOT and the CAIC look ahead to the future, it’s critical that there are no more CDOT workers injured or killed on the job, as well as the traveling public. With this in mind, there have been an increase in alternative mitigation strategies implemented and many that are in the future. In short, more remote operated systems are going to be utilized in avalanche mitigation on the highway systems. More GAZEX, which is propane and oxygen ignited, sending an explosion downward onto the top of the snowpack in the start zone. There will be more OBELLX systems installed, which are similar to the GAZEX, only smaller, easier to maintain and mix oxygen and hydrogen to create an explosion. The combination of these two systems will eliminate the use of the howitzer along the I70 corridor. That’s a big deal.

This chart helps to gain understanding of all the considerations for different mitigation strategies. “RACS” stands for “Remote Avalanche Control Systems.”

Other strategies that are being looked at for the future involve passive mitigation techniques (snow sheds, avalanche guards, etc) and an increase in remote operated systems (Wyssen Towers, Catex cable delivered explosives, etc). This will allow for numerous more options for mitigation strategies. So next time you drive your Colorado state highways, tune in more to your surroundings and all the work that is done to keep you moving safely to your next destination.

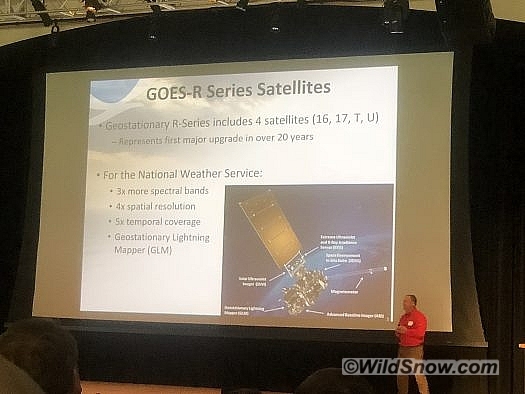

New Forecasting Tools for Colorado

This was one of the more interesting topics at this year’s CSAW. One of the big updates to weather forecasting for the National Weather Service is the installation of 2 new satellites. The GOES R Series satellites (GOES EAST and GOES WEST) are geostationary satellites that are fixed in place 22,000 miles above North America. Currently GOES EAST is in position and sending accurate information, GOES WEST is still getting dialed into its correct position over the continent. In short, here are a few of the updates to the technology:

The updated technology and resulting imagery/resolution information that we have access to dramatically increases forecaster’s ability to differentiate cloud types and precipitation types. This represents the first major upgrade to our weather satellite technology in over 20 years.

To my understanding, as it relates to the coveted snow accumulation predictions, the High Resolution Rapid Refresh Variable Snow-to-Liquid Ratio Algorithm is drastically improved to give us more accurate predictions based on model algorithms.

For all of you weather nerds and aspiring weather nerds (which we all should be), here are several free online platforms to gather weather information.

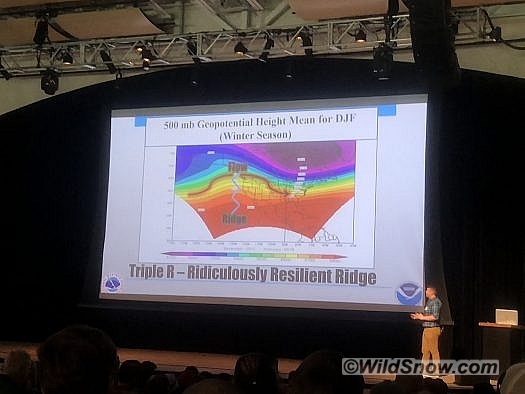

Ridiculously Resilient Ridge

The topic everyone wants to know, and no one in Colorado wants to relive. Meteorologist Jimmy Fowler recapped what happened in Colorado last winter, and what contributed to it. 2017/2018 winter was the 8th worst winter in the state’s history in terms of lowest snowpack at 68% of average (maybe this is optimistic for some of you; it has been worse!) This was largely caused by a “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge” of high pressure that sat of the south coast of the United States for the majority of the winter months.

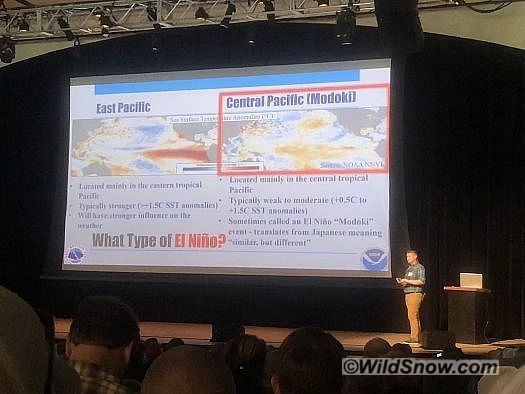

This ridge of high pressure was so strong that most fronts carrying moisture were deflected and unable to break through to the southern mountains, hence California and Colorado’s majority drought year. After a brief flashback to what was, Fowler offered up the current predictions of what 2018/19 will bring us in terms of a long-term forecast. At this point, experts are calling for a 50%-55% chance of an El Nino weather pattern by the Fall; this is expected to increase to 60% by winter. I’ve mostly heard of La Nina and El Nino weather patterns, but new information to me was the type of El Nino pattern. This winter is being referred to as a possible Modoki El Nino weather pattern.

Typically, El Nino patterns are positive for the Colorado Rockies, however, a Modoki El Nino refers to a typically weak to moderate effect. The Central Pacific is where this weather pattern is forming (as opposed to a strong El Nino forming in the East Pacific). As this relates to our winter weather predictions (snowfall); slightly better odds of Southern Colorado being wetter than average, and better odds of Colorado being warmer than average. Meteorologists are predicting that the state will have a strong start to winter through early January, and then will taper off dramatically leaving the total snowpack amounts below average by the end of the winter. Before you start throwing tomatoes at your screen for continuing to pass on unpopular information, it’s just a prediction, right?!

The day’s wrap up began with a study on changing ski season lengths as affected by rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere, which was interesting in terms of the data and timelines associated with our future actions as a species.

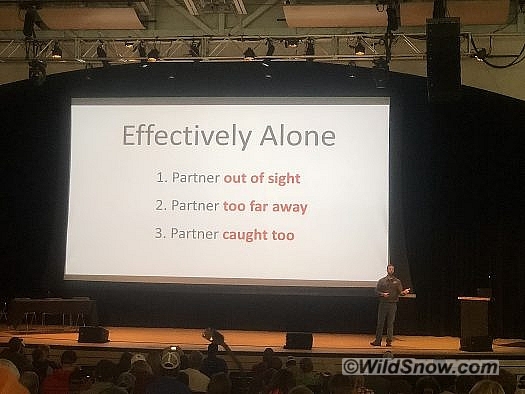

The final topic of the day, presented by Mark Staples, presented case studies and considerations surrounding avalanche incidents in which people have ended up effectively alone. Mark’s examples caused one to think about the realities of an avalanche accident and what resources you actually have.

Overall, the 17th annual CSAW was a full day of engaging and worthwhile presentations, made all the more interesting with a conference hall packed full of dedicated individuals to understanding the world of avalanches and avalanche safety. I highly encourage everyone to attend a workshop in your region to stay engaged and up to date.

Jonathan Cooper (“Coop”) grew up in the Pacific Northwest and has been playing in the mountains since he was a teen. This was about the same time he made the fateful decision to strap a snowboard to his feet, which has led to a lifelong pursuit of powdery turns. Professionally speaking, he has been working as a ski guide, avalanche educator, and in emergency medicine for over a decade. During the winter months he can be found chasing snow, and passing on his passion for education and the backcountry through teaching avalanche courses for numerous providers in southwest Colorado, and the Pacific Northwest. Similarly, his passion for wilderness medicine has led him to teach for Desert Mountain Medicine all over the West. If you’re interested, you can find a course through Mountain Trip and Mountain West Rescue. In the end, all of this experience has merely been training for his contributions to the almighty WildSnow.com.