If skiing is good, more skiing is better. If skiing is fun, skiing one mountain after the other, for miles and miles and week after week is more fun. In late April and early May of this year, I skied, mainly solo, California’s “Red Line Traverse.”

How best to ski the seemingly limitless terrain of California’s High Sierra in the spring of a fat year? Get high, stay high, and never stop moving. Looking south from Mount Powell or ‘Point John.’ 13,364 feet. 4/28/2017.

The Red Line Traverse has near-mythical status. There are as many definitions of the route as there are discussions of the line. Even the original protagonists were vague, seemingly intentional in their evasive descriptions. No matter, as the consensus seems to be that a traverse in the Red Line spirit would involve tons of skiing, on peaks, cirques, couloirs, and chutes along the crest of the highest portion of the Sierra Nevada.

What we know is that Tom Carter, Chris Cox, and Allan Bard, with a cast of others from one season and trip to the next, connected the peaks above Lone Pine to those above Mammoth Lakes. Carter and Bard, in the November 1983 issue of Powder magazine, map out the line with the poetry of vision rather than the prose of prescription.

“The initial idea for our ski was inspired by the notion that we could string together dozens of exciting ski descents like so many pearls… we crossed nearly fifty passes and climbed more than twenty peaks, rarely dropping below 11,000 feet… This was the land of full-certified, high-speed traverses and ultimate fall-line skiing on perfect snow.”

Looking ahead. Always looking ahead. A perpetual motion ski tour like this is an exercise in route-finding-as-sight-seeing.

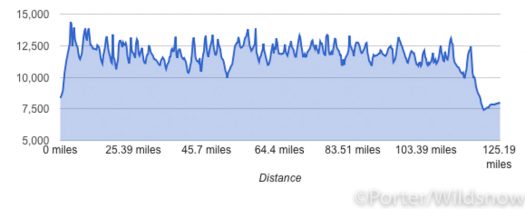

Red Line Traverse was the most physically demanding effort I have ever undertaken. The numbers (16 days, 125 miles, 79,100 vertical feet) tell part of the story. I had the company of two friends to the middle of day 2, one of them continuing on to the middle of day 4. I also have the moral support of spouse, friends, and family, and the material support of a handful of sponsors. But most of the trip was largely solo, taking just two resupplies, and camping out the entire way adds body to the description of the effort. Accumulated effort, altitude, and snow-sleeping further drained.

Day 2, April 19, 2017. My 38th birthday, incidentally. Ian McEleney points out our route down the NW Face of Mount Whitney. He, Sam Fletcher, and myself skied that before Sam took off over Whitney/Russell Col. Ian and I continued on that afternoon using Mount Russell as a pass, in the spirit of those that went first.

What, now that I’ve been there, is the route, exactly?

First, in general terms. I stuck close to the crest of the Sierra. The highest peaks of the range divide the watershed of the Pacific from that of the Great Basin. This ridgeline also divides California counties, as well as National Parks from National Forests. On maps, these boundaries, for the most part, are marked with a red line; hence the name.

I skied the best and rowdiest lines I could. I skied most peaks and routes up one side and down the other, moving forward. Bard and company specifically mention skiing the NW face of Mount Whitney and “Mount Russell used as a pass.” So I did those things. Photos in magazines and the ads of their sponsors from the time show them skiing the N couloir of Mount Humphreys and a couloir into the Palisade Glacier. I skied those too. They say they skied at least 20 peaks. I did 25, for good measure. I left the crest only when it meant better skiing. And, once, when leaving the crest by a little over a mile meant I could skip sketchy free-solo rock climbing, I steered even further from the Red Line.

The “founders” purposely kept their description vague, empowering future suitors to spend “day after day, hour after hour, on our knees fondling the topo maps.” I’ll do the same, honoring the perspective of Todd Eastman from the BackcountryTalk forum. “I imagine Allan would be most stoked by a party employing the spirit of the Red Line rather than the exact route … Always remember, an act of creativity like route finding in a natural setting can be deeply satisfying, even when following a generalized route. Don’t forget the whimsy and fun of adventuring as conditions allow.”

That being said, it could well be time to demystify the Red Line, letting the next generation of skiers step past this into bigger and rowdier creative interpretations of the Range of Light.

If you want to know exactly what I skied, I’m glad to share that individually. After all, like Lou says in his book, WildSnow, about California’s traditionally reticent skiers, “One would hope they will share their treasures, to give us our legends.”

You can’t ski the Sierra in a big year without lusting after the famous steep couloirs. In looking back through my journal, I count 25 proper ski lines. Most of them were steep, most were rock-walled, and most had excellent snow. All were north facing, all held wintry snow (until the very end. The Bloody Couloir was a corn run for my final ski descent). Only once did I climb what I skied. Every other ski run was done “top down” with the overnight pack, an “ever forward” mantra, and an educated guess as to conditions and route-finding.

Gear I used is listed here.

An obscure couloir on an amazing, prominent ski peak on day 5. Narrow, steep, with wind-scalloped powder snow and completely invisible from any road or trail.

I aimed to ski at least one “proper” ski line and to summit a peak every day. Only one day did I fail to summit a peak. But I was indeed able to ski real, worthy terrain every day. Some climbs were “for real,” with steep and firm snow mixed with classic Sierra rock scrambling. I spent a ton of time in steep terrain, up and down.

Overall, this was an athletic endeavor. At times the terrain was serious, but I was always minutes from flat ground and hours from dry desert. Athletically and technically this traverse was harder than all the Alaskan, Canadian, European, Greenlandic, and South American expeditions I’ve been on.

From an objective hazard, logistical, and commitment stand point, however, the Red Line of the Sierra is pretty casual. I’ve joked that, in rock climbing, bouldering is reputed to be low commitment but I argue that one has to be more committed in that venue than in serious alpine climbing. On an alpine climb, one must start a route, and muster appropriate motivation, only once a week or so. Bouldering one must start the route maybe tens of times a day.

Sierra enchainments (like this one, and alpine traverses I’ve done) don’t have the commitment factor of routes in the “Greater Ranges”. However, the terrain is similarly draining, and the opportunity to bail is almost ever present. One’s mind is constantly faced with the easy out. There is great liberty and confidence borne of repeatedly finding the motivation to keep going, even when there is an easy out. We test different parts of ourselves with different sorts of mountain endeavors. Low commitment enchainments like the Red Line truly ensure that one actually enjoys the here and now, as the opportunity for a different scene is ever present.

Solo skiing isn’t really that photogenic. That being said, the light and magic of the High Sierra make up for that. When the snow and scene is like this, it is hard to pass up an opportunity for an action shot. Action selfies are a skill all their own.

“This day and age” it is the fall-line ski runs that catch our attention. Couloirs and steep faces captivate the attention of our ski mountaineering community. One of the directives of the Red Line’s original activists was to “red line the fun meter”. In other words, seek the most enjoyable, laugh-worthy experiences in the sliding world.

Call me a curmudgeon, but steep, often-firm, wilderness skiing with an overnight pack and lightweight ski gear isn’t in my definition of fun. It is satisfying and thrilling and I build huge portions of my life around it, but I don’t find myself spontaneously laughing out loud. It is the long glides that are the Type-1 fun, “giggle pow” of multi-day ski mountaineering. To launch from a high saddle or turn onto the debris fan of a splitter couloir and glide for miles just above the flat lakes and lumpy moraines, covering literally tens of miles an hour is pure bliss. On Sierra “wind board” and corn, whether frozen or softened, the glide ratio of a mid-weight rider is pushing 10:1. Need to cover a mile? All you need is a line gently crossing the contours for 600 feet or so. Firm snow, a careful plan, and some edge angulation gets you, literally, a long way.

I hit snags. Of the world’s major mountain regions, California has relatively excellent weather. My time window was blessedly free of any “atmospheric rivers,” but the minor poor weather nagged a little. Day one, for instance, was forecast to bring “less than one inch of accumulation”. We skied Whitney and Russell in almost a foot of powder. I got blown to the ground a handful of times at Taboose Pass, battling clouds and spitting graupel mixed with rain for 3 hours and 600 vertical feet of action and then 20 hours in a hastily scraped snow hole. The final pass of day ten took me onto the west side. A fully clear day segued to complete, unyielding white out that lasted until first light the next day. By the final two days the freezing line was creeping up into five digit altitudes.

Spring Sierra skiing is largely done in good weather. Nonetheless, there are occasional fits of more alpine conditions. This particular morning, an all night whiteout in gentle winds resulted in some riming.

What do I have to “claim”, if anything? The web is full of chatter about the Red Line traverse. Guidebooks and magazines mention it. Its “unrepeated” status seems pretty certain. The original crew did at least some of the route in what is still a record-setting snow year. They had coverage that might not have been replicated until this season. Others certainly claim traverses of the Red Line. Sierra ski historians reference “unrecorded” completions, done under the radar.

Even my own effort could be completely different than the original. For instance, the original Red Line is reported variously as “Whitney to Mammoth” and “Langley to Mammoth” (the latter is just a little bit longer). I skied Whitney to Mammoth.

The original traverse was done by a rotating cast, over at least two seasons. One repeat since then skipped at least some of the major ski lines we know Bard and company did, and came out of the mountains for a few days of r and r. The activists of one rumored repeat did so in 2016, a year in which some of the major ski lines weren’t filled in. I haven’t heard back from them about what exactly they did.

In the end, for the history books (and, remember, WildSnow was first a history book…), this stuff kind of matters. For the individual effort, though, it doesn’t.

To be sure, the allure of doing something first is powerful. However, anyone that’s been out for days and weeks on big missions knows that that allure is tiny motivation, if any. It is hard work, stunning landscapes, and profound, transformative adventure that keeps a body going. I have done more research on the history of the Red Line in the week since finishing than I did in the years prior. The idea that I could be first was strong, but the actual fact of the matter wasn’t important.

Little is as satisfying, frightening, draining, and mystifying as being a tiny human, all alone in a huge mountain wilderness for weeks at a time.

Overall, the Red Line was a grand ski adventure. Like the experience of the visionaries, it is one of the coolest things I have ever done and is something I have wanted to do for a long, long time. I hope that others can follow suit, and only raise the bar further. There is more to ski, and room to improve the style, considerably.

Bio. Wildsnow guest blogger Jed Porter is a full-time, year-round American Mountain Guide and is slowly putting down roots in Idaho’s Teton Valley. He skis, climbs, and eats. He’s happy to do the same with you, through Exum Mountain Guides, his own company, and a host of local partners around the continent and world.

Jed Porter is a passionate adventure skier and all-around mountain professional. His primary work is as a mountain guide, skiing and climbing all over the Americas and beyond. Learn more about him at his website linked below.