Note from Lou: Upon perusal of the 2017 Skialper Buyer Guide, I realized their testing of binding release values was both difficult to understand, and alarming. Fact is, researchers such as Skialper are finding that tech bindings can produce some rather whacked out results when placed on a machine that measures release-retention values (“DIN” settings). I asked Skialper editor Davide Marta if I could take a stab at making a clarified edit of his English language pages regarding this situation. The full digtital desktop flipbook publication is available at http://mulatero.it/buyers-guide-2017-apertura/ — for smartphone & tablet download the free app iOS and Android and go in the ‘English’ tab to buy the English version.

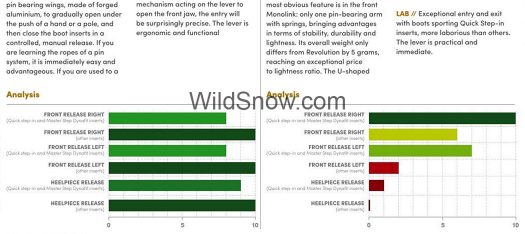

The magazine, where this all comes from is a series of bar charts (excerpted above) that compare tested binding values to those indicated by the printed scale on the binding housings. Some bindings were remarkably close, while many were whacked. Full length green bar means the binding matched up well, then it gets worse from there with shorter bars trending to red. The bars express a percentile. For example, if the bar goes to 10 the binding settings were quite accurate, while a bar at number 8 means the settings were 20% off from what the machine calculates as optimal, and so on down to the left end of the chart. (The bar chart release direction terminology is confusing. “Front” is lateral-side release, while “Heelpiece” is upward-vertical release.)

THESE ARE NOT SAFETY BINDINGS

words by Davide Marta, English translation edited by Lou Dawson

In the last (2016) edition of the Buyer’s Guide, we introduced evaluations of the side (lateral) and upward (vertical) release of ski touring bindings. This was an important development, in that it was — and still is — the only such test published at an international level. Our results were wildly popular and subject to much discussion among core backcountry skiers.

This year we did the same testing. Thanks to the Italian Wintersteiger branch, we were lent the Drivetronic machinery to test all 32 “2017” bindings we selected. (Note: We only selected and tested frameless “tech” bindings using the boot toe and heel fitting system invented by Fritz Barthel, and we use the terms “tech” or “pin” interchangeably to indicate such bindings.)

Important foreword: The pin tech binding situation remains the same. In most cases, manufacturers do not have an entirely relevant DIN/ISO standard they can refer to, nor good answers for customers asking how the binding they are about to buy will fare in case of accident or a fall. Amid all this, some skiers are fine with the situation; they figure their bindings simply do not have terrific release-retention characteristics and enjoy the gains in efficiency as a tradeoff. Other skiers may assume, wrongly, that their tech bindings are performing at the same safety and retention level as alpine bindings.

In other words, most of these products can not be correctly termed as “safety” or “release” bindings. Exceptions are Dynafit Radical 2.0, Dynafit Beast 14, Marker Kingpin (We did not test Vipec due to legal issues in Italy), which are the only models having received TÜV certification to DIN/ISO standard 13994. That being said, we make no assertion that TÜV certification always indicates a superior binding, we simply mean that the terms “safety” and “release” are only appropriate when the binding has had some form of standardized testing using established industry norms.

(For bindings without TÜV certification, confusion arises because in the case of non-certified bindings, manufacturers imply that the numbers printed on their bindings still correspond to industry norms. While some makers do attempt their own testing and calibration to make this so, that’s not always the case and as a consumer you have no way of easily knowing for certain. Our tests are intended to help with this, by showing just how close the “release” scale printed on the binding matches industry norms.)

Our agenda here is not to draw a conclusion about ski touring binding safety. Instead, we simply desire to show the state of play as it emerged from our tests, consistently executed with the same professional machinery used by many ski shops.

Let’s make an in-depth analysis of what the Wintersteiger Drivetronic is for: According to current DIN/ISO norms, it allows the input of skier data (boot shell length, weight, height, technical level and type of activity on the snow) to obtain a “Z value,” which according to the DIN norm is the number you adjust the binding to for optimal performance in retention as well as safety in case of a fall. To use the Drivetronic, the technician first adjusts the ski binding to the recommended Z value using the scale printed on the binding housing. The ski with binding is then mounted in the machine, which applies force to the binding, then ejects a printed receipt comparing actual binding performance to the Z value calculated from the skier data.

(This process may sound too rigid, but factors defining the Z value include an adjustable “Skier Level” setting with 4 levels that ostensibly compensates for more energetic “expert” skiing. For those of you who have never calculated a Z value, this DIN settings app seems to work. It calculates the setting used by Skialper to be about 6.5, based on the parameters Skialper shared at the end of this post.)

In alpine skiing, where regulations are more precise, in some countries the receipt printed by Drivetronic acts as a warranty: in case of accident or injury with the bindings adjusted following the criteria set by the machine, the manufacturer can be held responsible (what’s more, the warranty of some companies is only valid if the binding has been checked before use). If the binding adjustments have been even slightly modified, with regards to what the machine indicated, the skier is then fully responsible of his or her actions. The receipt given by Drivetronic is printed, signed by the client and then attached to rented or purchased binding. This can be a big deal.

The Drivetronic has “ski touring” as one of the choices in the control settings (according to the ISO 13992:2006 norm), so we tested all our reviewed ski touring bindings with the machine set that way. Once we inserted data relating to size, weight, foot size and technical ability, we obtained our Z value and tested the upward and side release. The machine answers “Good” if the force applied to release the boot corresponds to (or is very close to) the Z value. It responds “In use” if the force varies within an acceptable range (with a tolerance of about 20%).

If the Drivetronic force required for release deviates more than about 20% (up or down), the machine does not print a receipt. In the case of a customer, you would attempt to adjust the binding until the machine showed acceptable results. In our case, when a receipt was not printed we read the Nm (Newton meter) torque value from the machine display and used it to build our bar charts (histograms).

The bar charts here in the Buyer’s Guide simply show how much the actual tested values vary from what the binding is set to according to the scale printed on the binding. This is incredibly important. For example, if you think “I ski with my current bindings set on 8, so I’ll set my new bindings on 8,” our tests indicate doing so with some bindings may result in settings that are substantially different than what you may assume. This can work both ways, either making the binding overly resistant to “safety” release — or more prone to accidental release.

There is more. If a pin (tech) touring binding is released, not only does spring loading of the binding parts play a part, but all other flex in the system influences things as well. Touring boots play a role, with soft plastic compared to alpine boots. Flexing of the ski topsheet plays a part, as does the structure of the ski itself. Such variations can make comparative testing quite difficult.

Thus, we mounted all our test binding on hardwood planks of the same length. We then used boots from the main manufacturers on the market (Dynafit, La Sportiva, Scarpa, Scott, Salomon, Atomic, K2, Fischer, Dalbello, Arc’Teryx), with and without the various types of Dynafit boot fittings (Quick Step-in, Master Step, and original).

At the end of our tests we had hundreds of Drivetronic results. As mentioned above, we then built our charts using the data from the Drivetronic. The results were at times astonishing: We often obtained very different values on the right or left upward release. Sometimes, a boot with Quick Step-in fittings resulted in values substantially different than those we obtained with other fittings. Some of the fixed release (non adjustable) bindings were surprisingly consistent, though of course only appropriate if the fixed values are those you desire.

(Remember also that our results are from limited combinations of bindings, types of fittings, and boot models. Going beyond that would be a mammoth job — and perhaps not show anything more than what we already have.)

What is the take away? Everything and nothing. First, the bar charts do not necessarily indicate a binding works well or poorly, in most cases they only indicate whether a binding might possibly require more or less care in how the retention-release values are set. Clearly, the lesson is you should be very careful in how you assume a ski touring binding is performing in terms of retention and release, and have bindings tested if at all possible.

Moreover, when you mount a pin tech binding, you should not think that you are buying a “safety” binding (apart from a few possible exceptions). Consumers need to be aware of this; when they’re shopping they deserve to be informed by the retailer. Pin tech bindings should be chosen for performance, lightness and practicality — not assumed to be “safety” bindings in the sense that alpine bindings are. The next step is up to the binding manufacturers. Whoever crafts an efficient touring binding, which guarantees release values in case of fall, avalanche, or accident, albeit ensuring against accidental release, will be the winner of the gold rush.

The binding analysis was carried out setting the Wintersteiger Drivetronic software with the following criteria. Again, note that if a binding tested out of gamut and the machine did not supply a receipt, we got our data from the machine’s display.

– Sole 305 mm

– Skier weight 67/78 kg

– Height 167/178 cm

– Technical level 2/4

– Age 20/50 (no junior)

See our review of the 2017 Skialper Buyer’s Guide.

Beyond our regular guest bloggers who have their own profiles, some of our one-timers end up being categorized under this generic profile. Once they do a few posts, we build a category. In any case, we sure appreciate ALL the WildSnow guest bloggers!