Andre Roch, 1937

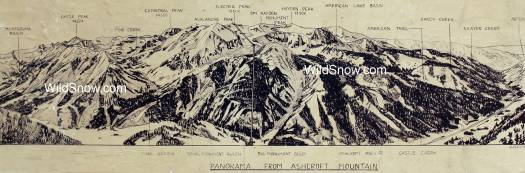

Andre Roch 1937 plan for developing skiing in the Castle Creek Valley out of Aspen. The ‘Ski Hayden’ and ‘Hayden Peak’ labels are reversed. Note the amazing tramway he proposed, which rivals modern cable on Whistler or Snowbird! We’re glad it wasn’t built, Hayden is some of the best ski touring near Aspen. Click to enlarge.

Editor’s note: Aspen, ASPEN, known to the entire world as easily one of the top five or so glitz ski resorts (Cortina comes to mind…). It wasn’t that long ago that the “A” town was bereft of ski lifts and struggling in economic depression after the U.S. demonetized silver. In 1936 a group of investors, including wealthy heir Ted Ryan, hired Swiss ski champion and alpinist Andre Roch to research and guide opportunities for skiing in the Aspen zone. Roch was attracted to the high alpine in the Elk Mountains between Aspen and Crested Butte, but WW2 intervened and nothing much came of the European alpine zone skiing he enjoyed and promoted for the Castle Creek Valley. Instead, after the war Aspen skiing was developed in the 1940s among the brush and mining ruins of Richmond Hill, rising directly south out of Aspen. (After many years of infrastructure improvements, trail cutting and land contouring Aspen Mountain is one of the gems of North American skiiing, but due to global warming, its low elevation could eventually spell its demise.)

But Ryan, Roch and their associates were the first to bring attention to Aspen as to skiing. Roch wrote the following speech and report that was distributed in 1937. The gold here is Roch’s descriptions of early ski tours he did on Hayden peak and other routes in the Elk Mountains, and his bold trip up Lost Man Creek and over into Aspen on the day before New Year 1937. His picture of what life was like in the Roaring Fork Valley before tourists and after mining is amusing as well.

The following historic document is lightly edited and annotated by WildSnow editors.

Introduction — Roch Arrives in Aspen

On the 10th day of our journey from Geneva via Paris, Cherbourg, New York, Chicago, Denver and Glenwood Springs we roll through the heart of the Rocky Mountains. Another few miles, and we’ll be at Aspen, Colorado. The night is black as ink, our car shoots at high speed over the distance, our headlights silhouette a group of deer — another halt; Tom loads his rifle, Bill lifts it, aims and shoots. One deer is hurt, the rest jump the barbed wire fence and tear off into the night. Blood traces over the fence into the meadows. We try to hide the blood as best we can; fines for hunting out of season are high. One o’clock in the morning we drive into Aspen. The first impression is sad; the town is empty and dead, there is no snow, but an icy December wind drives dust through the streets.

(W.S., Roch was with Tom Flynn and Bill Fiske; Fiske was perhaps the first United States citizen to die in WW II.)

Aspen was born nearly 60 years ago (W.S., founded circa 1877; when Roch visited some of the town founders were probably still living!). The first trappers and miners arrived from the south, always fighting Indians, via Ashcroft or through Leadville and Independence Pass. The found lead, zinc and silver so that Aspen soon developed into a splendid location.

In no time at all the town was built and soon it counted about 12,000 inhabitants. It was here in Aspen that the richest silver mines of the United States were exploited. Of this boom period, the most magnificent stories are told of Aspen. Unlike the shady characters so common on the trails to gold or oil, the migrants who built Aspen remained remarkably honest. (W.S., We don’t know where this odd take comes from, as the vast majority of mining money was based on pure speculation, not to mention downright fraud, according to historical texts we’ve studied.)

Money flowed easily, and the bars, dance halls and vaudevilles flourished. There was even an opera house where Sarah Bernhardt came to collect her share of the boom. The inhabitants of “Main Street” had their carriage, their own driver.

Then, at a given moment, the price of silver dropped and there was a terrible crisis; mines were abandoned, mine-owners fled and the miners themselves wandered off to Cripple Creek, where gold had been found. Today there are only 700 residents left in Aspen and the majority of buildings are in disrepair or ruined; many can be bought for $30 or thereabouts.

The town looks depressing, especially so in winter. In summer, the lush vegetation hides the ruins. But among the many ruins, there are still some palaces which have been maintained, mute proof of the glamour of bygone days. Some mines are in operation too, but to reopen those that were abandoned would require vast sums — and the value of their production would be questionable at present. There are, however, those old miners and prospectors who cannot overcome their mining fever, who still hunt and dig for rich veins, big strikes. Usually they are quite penniless, but if by some misfortune they can dig up some dollars, they invariably waste them on new tunnels which usually run into thin veins or none at all.

Dr. Langes and I had left Europe in order to explore the Rocky Mountains to find the most favorable locations to ski. But when we were briefed, we found that actually our job was of quite a different nature. The location had already been selected — and we were instructed to verify its excellence, to check on terrain and climate to be sure this location permitted the launching of a big resort.

Roch Critical of Aspen Attempts to Develop Skiing

Unfortunately some serious errors had been committed before our arrival, and this complicated our work. Try to imagine a valley much like the upper parts of the Valais. In all this land, there is only one town, Aspen, which would be located like Viege (Visp), with the one difference that Aspen lies at 2,400 meters (7,280 feet_. the highest mountains, just as in the Valais, rise over 4000 meters and are located in the more southern chain (the Elk Mountains). The whole country is completely wild. Old paths which led to mines or Forest Service trails are the only means of access to the interior of these several valleys. About 6 miles from Aspen, along the banks of Castle Creek, a splendid hotel called the “Highland Bavarian Lodge” was being built.

(The Highlan Bavarian lodge is now a private residence that still exists in the Castle Creek Valley, it was not ski-in ski-out in a modern sense but was fairly close to the Little Annie slopes behind what is now the Aspen Mountain resort. The Little Annie slopes are problematic in that they face west and southwest; Colorado’s best commercial skiing is done on northerly slopes unless higher elevation helps mitigate the effects of sunshine on the snow surface.)

Dr. Gunther Langes was an early ski guru, he apparently went ‘native’ while in Aspen. His choice in getup could fit in well even today.

The group which invited us to the United States had formed a corporation in order to launch a major winter resort. Unfortunately, the location for the Highland Bavarian Lodge had been selected in summer. The majority of the slopes on which the winter vacationists were to ski faced south or west, and we found during the ensuring winter, these slopes can never be skied at this latitude, which is the same as Sicily’s. Even after the heaviest snowfalls, the strong sun and dry air combines to let the snow vanish in a flash. On the other hand, snow accumulated steadily on the north and east facing slopes and STAYED LIGHT AND POWDERY FROM DECEMBER TO MARCH.

At the Bavarian Highland Lodge, the slopes were so steep that the danger of avalanches did not permit us to carry on any skiing. If you can visualize that the forests reach to 1,500 feet, that above the treeline the snow is continually blasted by west winds, and that the slopes below, with their steep cliffs and deep gullies, look much like the valley of St. Nicholas in the valley of Zermatt — you will understand that we were not exactly in a skier’s paradise and that we did not look forward with enthusiasm to the winter we were to spend here. Worst of all, the corporation had already launched a full scale advertising campaign, and guests from Boston, Philadelphia, New York and Chicago were planning to spend their vacations at the Highland Bavarian Lodge and even planned to ski there. (W.S., bear in mind there were no ski lifts, all the lodge guests would be ski touring.)

To compound misery, the snows did not arrive all through the month of December 1936 and whenever we strapped on our skis, it was most damaging to their running surfaces because of the many tree trunks and rocks. (W.S., lack of early season snow is typical in Colorado.) We always returned dejected, promising ourselves that we would not venture forth again until real snows had fallen. However, we never could stand inactivity very long and soon we were out again hopefully searching for better slopes.

Bivouac in Hunter Creek!

The last day of December, we left to investigate a valley north of Aspen which we thought might carry some promise. We traveled by car on the road to independence Pass, to the entrance of “Lost Man Valley” which we climbed and then proceeded along a side-branch which through Hunter Creek lead us to a point above Independence Pass. This valley returns to Aspen; it is certainly 15 miles long; after the first, rather steep drops, it enters the forest where the fresh snow was very deep. Our return trip was strenuous.

Night caught us when we were still 6 miles from Aspen. We were at the bottom of a gully, the sides of which were vertical. Only the reflections of light from the frozen river permitted us to advance, hampered by giant boulders and fallen trees. When it became quite impossible to progress any further, we built a campsite. We started several large fires and were soon engulfed by clouds of smoke. One o’clock in the morning, the moon broke through and gave us enough light to proceed on our difficult march. A coyote tried to scare us with his piercing shrieks and howls which echoed from the surrounding cliffs. Finally, quite exhausted, we drifted back to Aspen at 5 a.m. in time to wish everyone a happy New Year. (This is the last leg of the Trooper Traverse route from Leadville, only Roch failed to take the shelf road route out of Hunter Creek and ended up in the steep section of the river dropping into Aspen.)

Early in January 1937, the Highland Bavarian lodge was sufficiently completed for us to live there. From there, our excursions were limited to tour Richmond Hill (Little Annie) in all directions. Richmond Hill is a small mountain facing the lodge. From it, a splendid view can be enjoyed, but for skiing it carries little promise. Its slopes are either too steep, or exposed to too much sun, or covered by dense forests or else battered by strong winds. The best slopes are certainly those running down into Aspen. But even there, the lower slopes are endangered by avalanches.

Historic Alpine Tour Skiing out of Ashcroft

Ashcroft is located at 11 miles from Aspen, at 2800 meters, on top of Castle Creek. The first miners arrived here from the south by crossing Taylor Pass, 3600m. Large mines were started. One of them is the “Montezuma” at 3800m, from where the ore was lowered by cable cars to the mills, which were operated by hydroelectric power. At one time, Ashcroft had over 8,000 inhabitants who drifted by and by to Aspen, when richer lodes were found in that location.

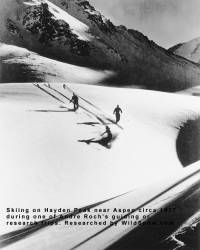

Nowadays there are only a dozen ruins left at Ashcroft and only one single inhabitant. As early as December, we came to Ashcroft and two things impressed us: firstly, Ashcroft is the center of a natural bowl surrounded by high peaks, most of them reaching above 4000m. Secondly, in this vast bowl the east and north facing slopes appeared well suited for skiing. The other directions are too steep or too wooded. During the month of January we had the opportunity to explore the slopes dropping east from Hayden Peak. The first steps were painful — frequently we lost our path in the dense forests and sometimes the hidden trees became a serious obstacle to the skier.

On the 15th of January 1937, I left alone from Ashcroft, planning to climb Hayden Peak, about 4000m high. It was a fine day, but towards noon, a strong wind came up and carried the snow into fantastic, turbulent shapes, leaving bare rock ledges. With luck I never lost the trail to American Lake; above, I came out into the open slopes. I climbed on over the bed of a former glacier, of which only the moraines are left, to arrive in a vast basin. I took off my skis and hid them in the snow so they wouldn’t be carried off by the wind. On the ridge, the wind was so powerful that breathing became difficult. Without further troubles, I reached the peak by following this ridge, only to find that the real Hayden Peak was still more than half a mile away and that the ridge would be rough to follow.

As it was 2 p.m., I had to turn around. I had a magnificent view of Conundrum Valley and in the distance many of Colorado’s famous 4000m peaks; Snowmass Peak, Maroon Bells, Pyramid Peak, Castle and Cathedral Peaks. I named my location “Ski-Hayden,” it is over 4000m high. (W.S. This is still called Ski Hayden and one of the most popular alpine ski tours out of Aspen, though most people use a different route for the Ascent.)

I climbed down rapidly and soon found my tracks in a small gully which we had explored a couple of days earlier. After this first success, we rarely had the time to explore any further: guests followed each other in rapid succession at the lodge and we had to act as guides for them. Though we knew very little about the region, we did have a few skiable slopes for them to use. On our trips we often ran across deer; skiing down noiselessly, it was possible to overtake them and ski right into the middle of their group. Coyotes were shy; one saw them only rarely. We were told that there are moose around as well as mountain lions, but we never met any. We Once saw a wolf from far away and another time a group of four mountain sheep.

The month of May is best suited for ski mountaineering. The snow softens in the bright sun, but as there is fresh powder nearly every day, conditions were superb. Dr. Langes climbed one peak north of Hayden Peak which he called “Frida Peak.”

A few days later, Billy Fiske, Dr. Langes and I climbed Hayden Peak: it was easily the most magnificent ski trip of the winter. The weather was fine, a foot of fresh powder covered the country. The dark blue shadows of the spruce and the sun dancing through the aspens made our climb an enchanting experience. Above the trees, the wide open slopes in which our tracks looked minute, offered the promise of superb skiing. We left our skis on a secondary ridge which we then followed with some difficulty to the peak. The view was quite overwhelming and I recorded it by panoramic pictures. The slopes leading down to Ashcroft can be compared with the best of the Parsenn. Immense “schus’s” where your face freezes in the wind and clouds of powder snow rise behind you, making the skier seem like a rocket shooting along the ground.

Hardly at the end of one schuss, we started into the next one, cheered by the fabulous skiing. Lower down we crossed a small forest, then we came to steep slopes which forces us to descent in short turns at the bottom of a gully. We returned to Ashcroft in less than 20 minutes, however we were still 6 miles from the lodge; luckily the road drops for most of the way. After our first ascent of Hayden, I returned there three times; once with skiers and instructors from the east; Otto Schniebs, Florian Haemmerle, Heinrich Scheinsbach, Bill Blanchard and Romison; another time with the best skiers from Denver, Thor Groswold, Frank Ashley; and finally with Aspen skiers Fred and Frank Willoughby and forester Clarence Collins. Each time, we felt the same enthusiasm, as no one had ever seen more splendid skiing country before. (W.S., We attempted to check name spellings, feedback welcome.)

After Hayden Peak, I climbed alone to the summit of the highest peak of the region, Castle Peak at 4300m. The climb was more demanding than Hayden Peak, but even more rewarding. The descent was again a series of basins and steps, one more regarding than the next. We had climbed up via Pine Creek and Cathedral Lake and skied down by the abandoned Montezuma mines. (W.S., this is the famed Montezuma Basin where you can find some of the most accessible high alpine ski touring in the Elk Mountains.)

Exploring Other Options for Aspen Skiing

After all these trips, I felt that I knew the region well enough to establish a list of all possible ski tours. We had the basic facts and valuable indications as to evaluate of the region as a potential ski center. But were there not, near Aspen, other slopes suitable for skiing which might at one time or another compete with our projected development? In order to answer this question, we began to explore the regions around Independence Pass as that road became usable again. In this way we discovered Green Mountain, which has splendid slopes but not enough vertical drop. We also climbed to Lost Man Lake to explore Lost Man Valley, where a 6 mile long valley drops rather mildly to offer an amusing trip.

(W.S., It’s interesting that a recurring theme in Roch’s analysis of skiing is his concern about “vertical drop.” This probably comes from his background in the Alps, and while valid is of course not as big a factor as he makes it out to be in terms of modern skiing, mechanized or human powered. Snow quality and physical access are greater concerns so long as terrain relief is reasonable.)

Climbing Colorado’s Highest Peak

Finally, the first day Independence Pass opened, Frank Willoughby and I took off in order to climb Mt. Elbert, 4400m, the highest peak in Colorado. We left Aspen at 2 a.m. and reached the pass in total darkness. Trenches 6 meters deep had been cut to open the road through the beds of numerous avalanches. We dropped down on the far side of the pass until Monitor Gulch. As we had never seen Mt. Elbert from near, we did not know yet from which side to attack it, though from studying the map we had planned a tentative route.

When we reached Monitor Gulch, we found that snows had melted too much to use our skis and we left them in the car. We climbed at first on a good path, which we had found quite by accident. Higher up, we crossed bare meadows, sparsely vegetated, then fields of hard snow which lead us to the ridge, from where we can see the peak. This is a giant mountain easy to climb from any side. After only 4.5 hours we are on top, surprised at the effortless success. A few days earlier, I had suffered from stomach troubles, which prevented me from enjoying fully this magnificent tour. We had a splendid and far reaching view. In the southeast, one can recognize Pikes Peak through the fog, most famed mountain of Colorado, and to the southeast the familiar mountains of Aspen, which are barely recognizable from this side. We take our usual panoramic views for our records and then descend again. To speed matters, we slide down vast snowfields, often sinking in to above our waists. Finally we find our car and return to Aspen; tired and content, I return to my bed to continue taking care of my health.

Conclusions

We have climbed many peaks, but still this is only a small fraction of the peaks in Colorado, which cover a much vaster region even than the Alps (W.S., actually not true). Nonetheless, as a result of our many explorations, some valuable conclusions can be drawn: The east chain of the Rockies does not receive enough snow to permit establishment of a winter resort (W.S., So true, to the detriment of attempts to establish resorts and ski huts east of the Continental Divide). The west chain is too low to offer good locations. (W.S., “West chain probably referes to the lower mountains west of Aspen, where Sunlight Resort is located, these areas are only good for snowsports at the height of winter, receiving quite a bit of rain in early winter and soon melting out in spring.)

Roch Recommends Ski Development of Ashcroft Area instead of Aspen

Thus remains only the central chain of the Rockies. ASPEN WOULD CONSTITUTE AN IDEAL CENTER TO OPEN THE MAGNIFICENT ASHCROFT REGION, which once developed would be a resort without any competition. Probably one could find other, equally splendid locations as Ashcroft in Colorado. However, the great obstacle in most cases is the fact that the valley floor rises to over 3000m as the peaks barely surpass 4000m this usually offers too little vertical differential. Another important point is the exposure of the slopes much more important here than in the Alps, because of the geographic location. West slopes are continuously swept by strong winds; south exposure slopes receive too much sun and are usually bare of snow. Remain only the north and east facing slopes, which are heavily covered with powder snow, sometimes too deep for comfort, for 4 months of the year.

Major Development Proposed for Ashcroft

Once the location had been firmly established, we devised a development of the ski resort as per the instructions received from the corporation. First of all, the road to Ashcroft must be totally rebuilt and in some parts relocated to evade avalanche danger. At Ashcroft, hotels capable of accommodating up to 2000 skiers, minimum necessary to make a cable care feasible, must be built. Besides the hotels, a Swiss village is projected with all the shops, cafes and offices found in a good winter resort.

A lift is planned on a ridge facing exactly north. On the northwest slope of the hill will be the beginners slopes and slalom glades. On the north and east facing slopes 2 or 3 jumping hills will be built, also a skeleton fun and sled course for children. The lift in this way will serve various purposes. Besides the lift, the cable car of over 1000m vertical rise will open unsurpassably beautiful slopes. The first (intermediate) station, 600m above the valley floor, will open up 4 different slopes of differing demands. The top station, 1000m above the valley floor, will open up a much vaster region and 8 different runs. Moreover, a variety of tours and of variations to these runs will be available, maybe 15 all in all.

The upper terminal, at 3800m elevation, will be equipped with another hotel which will offer spring and summer skiing. A special automobile service should be established to bring home skiers who used the long runs, not ending at the lodge. The most important runs will have a vertical drop of 1600m over a distance of 2.5 to 5 miles. The ski tours feasible from Ashcroft have been explored by us and a number more than 35. Keeping in mind that the country is beautiful in summer too, with fishing, horseback riding and camping available, many plains inhabitants will search out this country in summer. Add to this the deer hunt in fall, it is easy to see that America could find here a resort that would in no way be inferior to anything in the Alps.

But, let us not worry — the more Americans will enjoy skiing, the more they will want to visit our (European) alpine ski resorts. All we must do is to receive them well.

Roch photos in Der Schneehase ski journal 1937, Le Ski Club Académique (SAS) Genève. Click to enlarge.

It’s possible the first version of this article was published in Der Schneehase (pictured above), which to the credit of the Euro folks has been scanned and made available on the web. This link might go directly to the article.

(Note from Lou: Credit goes to Mort Lund for knowing this paper existed in translation and mailing it to me back in 1997 while I was working on the Wild Snow history book. I mention to Mort in a letter that I found it odd Roch didn’t mention he first skied on Hayden with a group of students from a the “Los Alamos School.”)

Beyond our regular guest bloggers who have their own profiles, some of our one-timers end up being categorized under this generic profile. Once they do a few posts, we build a category. In any case, we sure appreciate ALL the WildSnow guest bloggers!