After a few days of spectacular climbing (see Bugaboos Trip Report Part 1, Splitter Classics!), Coop and I took a day to laze around Applebee Camp before hiking over to East Creek Basin below the Howser Towers in Canada’s spectacular Bugaboos.

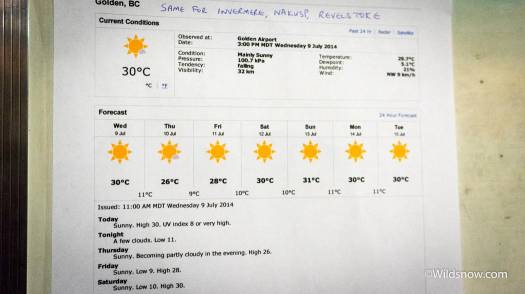

I glanced at the weather forecast as we left Applebee. Still 100% yellow circles for the entire period. Sweet!

But the Bugs had other things in mind, like teaching us a lesson about the accuracy of weather forecasts and what gear we should be carrying for alpine rock climbing.

We arrived in the basin to find our friend Hayden Kennedy and a few of his friends camped there, and no one else. A nice change from beautiful, but crowded, Applebee Camp.

After an evening of relaxing, we decided to wake up early to climb the mega-classic Beckey Chouinard route on the South Howser Tower. A bit before sunrise we noticed a few wispy clouds high in the atmosphere, a marked change from the clear skies we’d seen since we got up here. We briefly mentioned the change, but it didn’t look very threatening, so we continued.

By sunrise we were scrambling up the approach ridge to the impressive West Buttress.

The first pitches of climbing were incredible, although I was feeling a bit tired from the past few days of getting after it. We still moved quickly and made it up several pitches before the weather began to look more ominous. The clouds closed overhead, and hints of distant thunderstorms appeared on the horizon. We had a brief discussion, but at that point rappelling what we came up would have involved shenanigans and likely lost gear, so we decided to push on and attempt to outrun the weather.

As we climbed, once-distant thunderheads rushed towards us like a Biblical plague. Armageddon caught us two pitches from the summit ridge. Heavy rain pounded, and Coop, who was on lead, heard his ice-axe buzzing. As soon as possible he rapped down next to me. We were in a slightly sheltered gully. In a largely symbolic attempt at lightning avoidance, we clipped our harnesses and all our metal gear to the rope, hauled it a good 20 feet above us, and settled down to wait. Relying on the perfectly sunny weather forecast, we had left our rain jackets at camp. We were drenched in minutes. Luckily our light fleeces and synthetic puffies retained some warmth, but not much.

We shivered for two hours, resisting the temptation of numerous short sucker-holes, until one break appeared that looked promising for a run to the top. Barely stopping at the spectacular summit, we immediately began the 11 rappel descent down the imposing North Ridge. Cold, scared, and gripped by the specter of oncoming weather, we made three speedy rappels. Simul-rappelling and cranking the rope through the anchors, it was clear we weren’t going to outrun the dark wall of water racing toward us across the glacier. About four rope-lengths down, it hit us. Exposed on the crest of the North Ridge, we became thoroughly soaked, and exponentially colder than before.

Even then, I was psyched. We were on our way down, and it looked like we’d get off without too much more trouble. But, after a few more raps, things got serious (if they weren’t already). On our eigth rappel I was pulling the rope, and it stopped cold.

I cursed, and tugged lightly. Nothing.

“NO!” I whipped the rope around wildly, hoping to get it dislodged from the flake we could see high above our heads. After a few minutes, it was clear it wasn’t going any further.

“Well, we could ascend, try to climb, or….” I half-heartedly went through our options, but we both knew there was only one: cut it. The rappel route follows the North-East ridge, graded at A2. Looking at the water rushing down the face above us, our only choice was clear. Coop retrieved the knife from his pack, and unceremoniously sawed what at that moment was our most prized possession.

Luckily, the next rappel was a short one, and we managed to make it to the next set of anchors. Below us, two more 30 meter rappels led down over a gaping bergschrund and onto the glacier. We rapped as far as we could, set up a tenuous anchor with numbed fingers, and tied one end of our remaining rope to it. We made the final rap over the ‘schrund, through a newly formed waterfall (brrr), and onto the solid glacier. Coop cut what remained of our rope to use as a miniature glacier cord, and we set off at a sprint towards camp across the mushy, saturated glacier. Renewed activity was welcome and my body soon upgraded from bone-chilled to moderately frozen.

We hadn’t brought a tent to our East Creek bivy (go ahead and say it), so our plan was to grab our saturated camping gear, turn, and make the trek back to Applebee Camp. We must have looked as miserable as we felt. Our friends took pity on us and lent us their spare tent. Miraculously my down sleeping bag wasn’t soaked and I settled down to a night in relative warmth and comfort.

The next morning dawned clear and sunny. We dried our saturated gear, reflected on the previous day, and tried to avoid looking at our beleaguered rope remnant. Later that day we packed up and hiked down to the waiting car.

We had underestimated the gas requirements of the long dirt road up to the trailhead. Not wanting to run out of gas part way down, we stopped by the CMH Bugaboo Lodge, where an old-timer kindly put a few gallons in our tank. (Unfortunately I forgot your name, but if you’re reading this, thanks!)

Our troubles were not over. Late that night, nearing the US border, as we passed by one closed gas station after another. The gauge soon read dangerously low. After the requisite young-dirty-smelly person car search, we used the border guard’s phone to call AAA. After a few hours we had enough gas to get on our way. Early that morning we made it to Spokane, and a welcome, soft bed.

A harrowing epic, one from which I’ve gained experience and lasting respect for alpine rock. With a few small changes or more mistakes our adventure could have taken a turn into much worse territory, and I’m thankful we had it as easy as we did. I feel bad for leaving our rope and gear on Howser, however Hayden was kind enough to run up the route and clean our junk off a few days later (Thanks, man!).

Louie Dawson earned his Bachelor Degree in Industrial Design from Western Washington University in 2014. When he’s not skiing Mount Baker or somewhere equally as snowy, he’s thinking about new products to make ski mountaineering more fun and safe.