Many of you have tracked the great DIN. The elusive beast lurks under the pristine white counters of testing labs the world over, and winters in a monolithic brick building in Munich, signed with a large placard bearing the letters “TUV.”

And, along with you consumer stalkers, many a binding company has hunted DIN. Such hunts — rarely of total success — have cost millions of euros, at least several jobs, and are rumored to have led to at least one mental breakdown. The DIN has power.

The 13992 beast nests here, but is born under the wings of DIN/ISO (TUV-SUD press photo)

When I often wrote of the DIN hunt, not a month went by that I didn’t hear from a ski binding company going for a trophy. Then later, when their stalk failed, I’d listen, exasperated, as they attempted to obfuscate the true nature of the animal. I even heard tell of rival hunters, those who abhorred the dominance of a new mutation, who had somehow influenced the hunting regulations in an attempt to extirpate the two-pronged Dinachron variant. True? Who knows. But I wouldn’t be surprised.

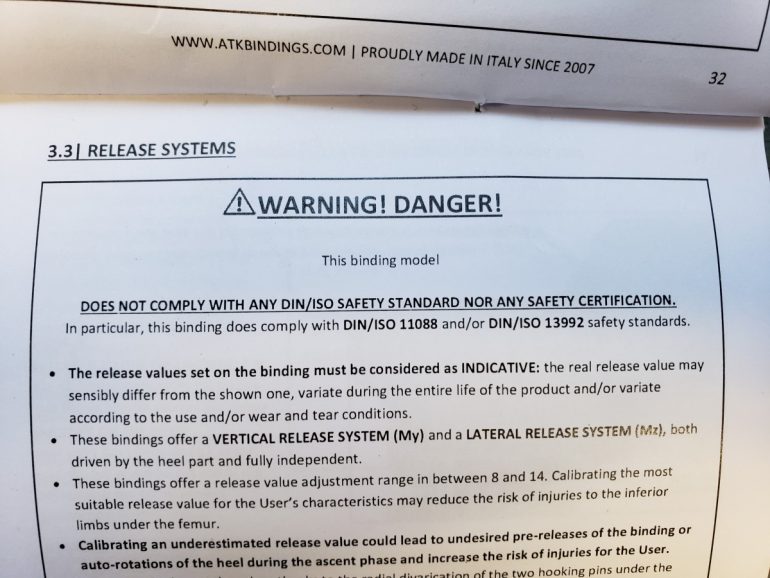

Even I, my dears, was once raked by the clawed paws of the monster. After the lacerations healed, I attempted to at least clarify the biology. Yet perhaps mistakenly implied that if a tech binding somehow conformed to even part of the DIN/ISO 13992 standard, it was somehow superior. I’m here to tell you that is NOT the case.

Some parts of DIN/ISO 13992 are useful to examine as a binding designer — and consumer. If for no other reason than awareness of issues such as icing, and elasticity. But the infinite variety of ski touring, from freeride to skimo, introduces so many conflicting safety issues and convenience features, the only way I can see a DIN/ISO tech-binding standard ever becoming industry-wide is if it’s broken out into numerous branches. Even then, could the white-coated engineers and keyboarding bureaucrats create such a thing? Prove me wrong, but I doubt it.

So, enter the binding companies (now the majority?) that ignore the DIN/ISO ski touring binding standard, and make bindings based on features and performance their customers want.

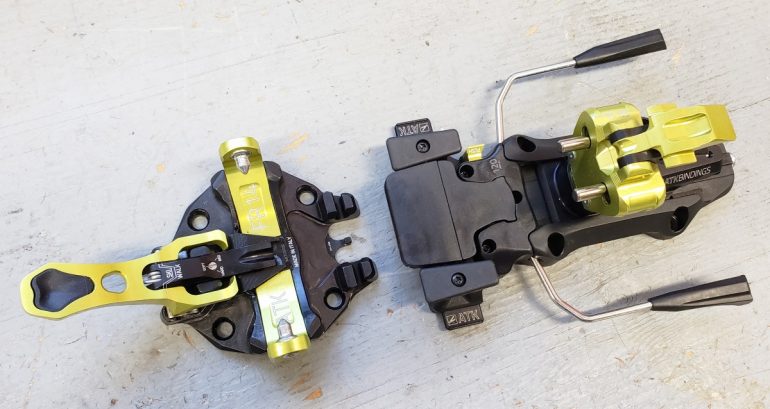

Case in point: ATK FR-14 Freeraider

With its built-in brake and freeride beef, the ATK FR-14 has been around since the 2019/2020 season (as well as building on its predecessor version 2.0, which was produced until the 2018/2019 season). It has survived consumer testing with high marks, and comes to the WildSnow shop for a long-awaited technical look.

Overall, this grabber glows with quality. Tool marks indicate the essential aluminum parts are mono-block machined, with a pleasant (if so Italian) sheen. A touch with my razor knife indicates the heel base and other plastic parts are plenty strong, no doubt carbon-reinforced. Before I get into the photos, here’s a bullet list of a few things that stood out for me:

— The upper part of the FR-14 heel unit, the part that rotates, has zero play, I mean a big fat ZERO. Other brands boast such quality as well, yet not all.

— The heel lift options are out of hand. Heel flat on ski; two medium lifts with the rotated pins forward; another two higher options with pins rotated rearward. Five total? Correct me if I’m wrong. On a personal note, with my fused ankle, I need fine-tuned lift on the uphill, this thing looks fantastic in that regard.

— Dynafit-type crampon compatible

— Flex compensation spring enhances the specified 4mm tech-gap

— And the weight. It is remarkably absent for this much beef (remember the brake is built-in):

— Total, one binding w/ screws, no stomp block, 366 g

— Total, one binding w/ screws, w/ stomp block, 392 g

— Heel, no stomp block w/ screws 240 g

— Toe w/ screws 126 g

— Stomp block assembly 26 g

In comparison, consider another brand’s proven touring binding, not a full-on freeride unit, yet competent, comes in with a no-brake weight of 296 grams, and tips the scale at 385 grams with brake!

Let’s blast a few photos; actually, more than a few.

The toe unit has ATK’s long time U.H.V. touring retention adjustment system. That’s TOURING, as in uphill. The U.H.V. allows you to set the pressure the toe pins exert on your boot toe sockets — while locked in touring mode, which translates to how hard you have to pull up on the locking lever to engage it. While I’ve rarely seen the need for such a system with other bindings, I suspect it’s important for ATK because their toe wings are so strong and precise. Thus, if a boot had fittings a little out of spec, without a way to adjust the touring-lock tension, the lock might be difficult to operate, or conversely, be hard to exit. The U.H.V. adds just grams of weight, if any. Clever.

And check this out regarding the toe unit. While open or closed, the area under the wings remains somewhat sealed, no more snow packing the space under the wings (though I suppose in rare cases you could get ice under there, which would then be difficult to remove).

I’ve added a new test to the Wildsnow probe-and-prod, metal hardness. While a set of hardness files is hardly the equivalent of a $21,000 Mitutoyo bench-top hardness tester, it’ll have to serve. The ATK toe and heel pins, testing between HRC 60 and 65, were just a bit harder than a good quality knife blade, and compared favorably to several other binding brands we have here in the shop. Bear in mind that pin surface hardness isn’t everything — it’s equally or perhaps more important they don’t break. Achieving surface hardness without brittleness isn’t child’s play — it’s where consumer testing tells the tale.

Let’s get into the brakes. So cool, so elegant. The photo above shows the brake retention system compressed with a clamp, so you can see the tiny internal hook that catches the brake when you stow it. A light press with a finger, and pop, the brake deploys for the downhill. Let’s be clear that mixing ski-brakes with tech bindings has been the elephant in the room for years now. I can’t tell you how many brands have attempted, and most often failed, to design a flawless brake that’s automatic or semi-automatic, that you can’t lock up in downhill mode, yet locks perfectly in touring mode. The DIN/ISO 13992 (if I’m not mistaken) does not allow a brake you can lock away in downhill mode. Is this one place where ATK said, “go fly a kite”? Quite possibly. In any case, as I’ve advocated for years: give us a manually operated brake and quit the fiddling around already.

I’m reluctant to get into the stomp block, or as ATK calls it, the AL09 Freeride Spacer, because the required raft of photos will probably melt our webserver. But here goes: I can’t believe how much design effort ATK put into this thing. I mean, I see how stomp blocks can help ultra-agro or ultra-huge skiers, but, really? Okay, I know, you freeride, you want a stomp block. Shut my mouth, and here come the photos.

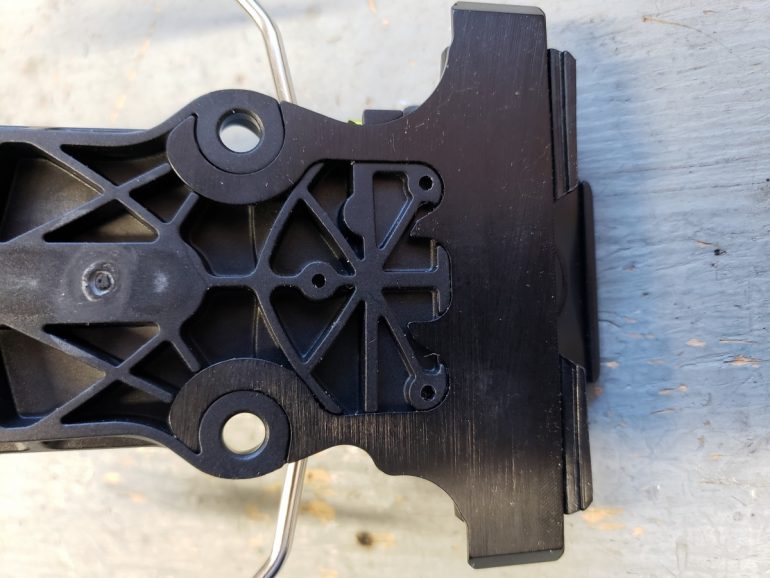

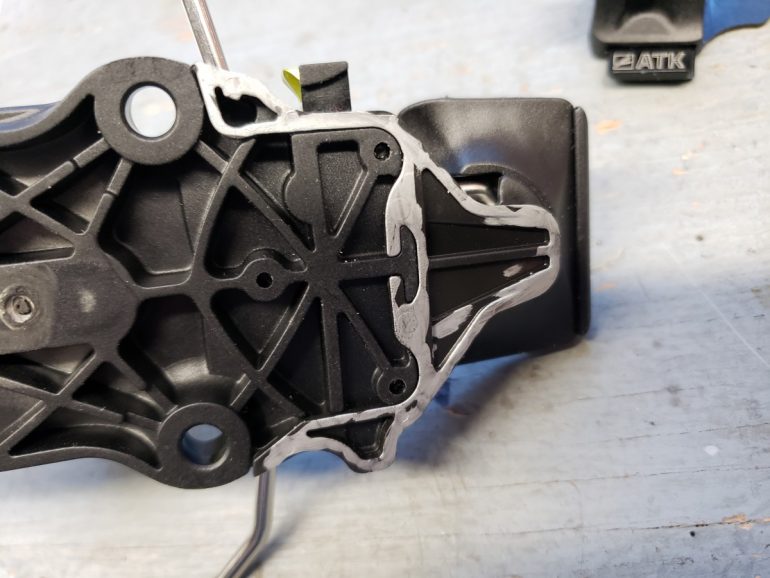

The stomp block is an optional, precision molded piece that nests with the heel unit like something made for the James Webb space telescope.

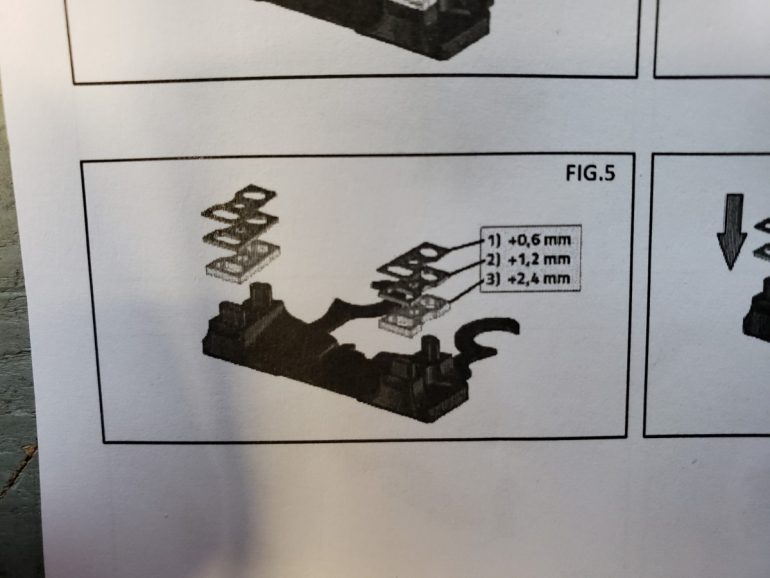

The AL09 Spacer isn’t just any space case, it’s tune-able with the included shims. Pictured above, you remove the stomp blocks with a torx driver, then shim as desired, though take care not to shim so much as to created upward pressure while the boot is in neutral position. I’d recommend leaving a thick paper width of clearance, or perhaps a millimeter.

Binding mount pattern is appreciated, all screws at 45 mm left/right distance, thus helping those who make paper templates.

I backed out the torsional release spring barrel. The Freeraider uses a pair of torsional release springs, buried deep inside the spring cavity. Here you can NOT see the torsional release springs, what you see is two coils of the flex compensation spring, as well as the shiny length-adjustment screw.

Last thing. We think toe jaw closure strength is important. It prevents pre-release, and may allow you to tour without locking your binding toes. I tested the Freeraider 14 on my “jaw puller.” It pulled a respectable 162.8 newtons, placing it in the middle of the range. In my experience, that’s adequate. Spreadsheet below.

(Please note, this post is in no way intended to disparage TUV, as they are nothing more than a company that tests products according to various standards — and are said to do a pretty good job of it. What deserves a critical view is the DIN/ISO system of product standards creation and upkeep, specifically regarding ski touring binding standard 13992.)

WildSnow.com publisher emeritus and founder Lou (Louis Dawson) has a 50+ years career in climbing, backcountry skiing and ski mountaineering. He was the first person in history to ski down all 54 Colorado 14,000-foot peaks, has authored numerous books about about backcountry skiing, and has skied from the summit of Denali in Alaska, North America’s highest mountain.