When you think of the right tools for the backcountry, what comes to mind? Lightweight pin bindings, the best AT boots, and the right planks for the conditions? When we step into avalanche terrain, which is plentiful outside of the ski area boundaries, we have to think far beyond what’s under our feet. If you’re reading this, you likely already know that WildSnow is a near panacea of resources related to gear. If you’re new; welcome and get to work!

Beyond touring specific gear, avalanche equipment can vary from essential to helpful and we need the right tools for the job.

When we think of avalanche specific tools, the most common trifecta of pieces of gear we hear is “beacon, shovel, probe!” To the untrained individual that is certainly the bare minimum and a place to start. We can view these tools from a problem = solution perspective. What is the problem we are trying to solve with a piece of safety equipment?

Here is a basic example:

Problem: your partner is caught and fully buried under the snow in an avalanche without any visual clues of their location.

Solution: you need to use an avalanche transceiver to locate their approximate location, a probe to pinpoint their exact location, and a shovel to excavate the snow around them to prevent asphyxiation. There are a whole host of nuances and additional factors to consider when it comes to the problems you may encounter in avalanche terrain. Most importantly, the majority of the tools and equipment laid out here are a reaction to an avalanche incident, not a prevention strategy.

Since we currently think of a beacon, shovel, and probe as the modicum of safety equipment, I’m going to start with proactive tools to help minimize avalanche incidents in the first place.

Partner(s)

Find a quality partner – someone who will keep your ego in check, challenge your biases, be a resource if the defecation hits the oscillation, and take great photos of you…

Is your partner an avalanche tool? The individuals you choose to travel with in avalanche terrain can fit somewhere along the spectrum from resource to liability, choose wisely! How many people do you travel with? Depends on the goals, and the conditions.

Beyond the obvious need to have someone who can physically locate you and excavate you, a partner can be one of your first lines of defense against a potential avalanche incident. A quality partner has numerous characteristics depending on your own personality and susceptibility to decision-making snares (problem). Someone who can offer a counter perspective, make and contribute meaningful observations, agree to a tiered plan approach based on observations, and agree to turn around when needed are all part of the deal (solution).

Additionally, choose a partner who dedicates as much stoke to being prepared with medical training, avalanche rescue, and general winter survival savvy as they do to riding powder.

Terrain Assessment and Communication Tools

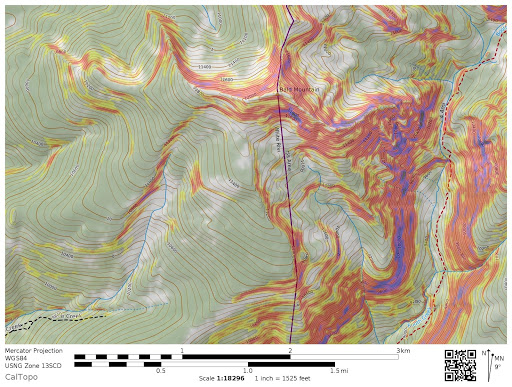

Your ability to assess terrain and conditions in the backcountry is paramount. I start this process from a macro level at home. Your local avalanche bulletin (get to know it well, especially the observations page), and your local weather resources – both past, present, and future are imperative. Online mapping and touring planning resources have changed our process for the better, but they are not the silver bullet. Desktop resources such as caltopo.com, and Google Earth are great. Quality resources will have overlays such as satellite imagery, topo maps, and slope angle shading (find one with Lidar). These will give you a place to start your planning before moving to a micro terrain and conditions approach.

Utilize desktop and handheld mapping tools as macro-perspective terrain assessment tools. Your ability to recognize avalanche terrain subtleties will depend on your knowledge and experience. Having analog backup tools such as a paper map, a compass, and an inclinometer can be important as well.

All of your time spent mapping at home is not useful unless you can reference it in the field. Your phone is a great resource as a multi-use tool (if it’s charged). Gaia GPS and the CalTopo app are effective for transferring GPS tracks and waypoints to your phone for navigation, and most phones have a built-in inclinometer app.

It’s critical to be able to use the tools, but not become tunnel visioned by the “blue dot syndrome”. Be able to measure slope angle and calibrate your own perspective, recognize terrain hazards that are right in front of you. Analog tools are worth considering such as a compass/inclinometer and paper maps, in case the technology ceases to function — which it will at some point.

Communication is critical in the backcountry. Analog communication tools may not be as effective as a radio…

Communication with your partner or outside help is crucial. Don’t be caught alone while in a group in the backcountry. Your plan will quickly fall apart if you’re separated or out of sight. Have a form of two-way communication that is not your phone. A radio with a shoulder mounted mic is preferable for ease of use. There are many options out there, and some are better than others (a.k.a don’t be lured in by the cheapest Chinese made radio out there, and make sure you’re aware of FCC rules and regulations). Communication with outside help when everything else fails is your insurance policy (speaking of…) and there’s no excuse not to have something. A Garmin Inreach Mini is what I carry with me.

Beacon

Your beacon should be a modern 3-antenna beacon with a marking/flagging function. Additional features will depend on what kind of user you are.

There are A LOT of beacons out there, and WildSnow has many reviews of current and past models that you might see. This piece of equipment is a standard part of your kit. The minimum features you should be looking for in a beacon are: modern (within 5 years), 3-antennae, and a marking/flagging function. (Check out our extensive beacon coverage.)

There are beacons that are approaching smart phone status, and they have their place with certain users. Keep it simple if you’re new, but the above features are the minimum. Maybe more importantly, don’t let your partners have a beacon that doesn’t fit the above parameters.

Shovel

There are many shovels on the market, make sure you and your ski touring partners have ones that meet a minimum criteria.

Similarly, there are numerous models and styles of shovels (see Lou’s recent picks), but the one you want to have should meet the following requirements. An avalanche shovel should be aluminum (not plastic), have an extendable shaft/handle, and be UIAA certified for quality and effectiveness. Other features you might see are an ability to go to “ho-mode” excavation. This can be effective, but I would not say it is a necessary feature for the tool.

Probe

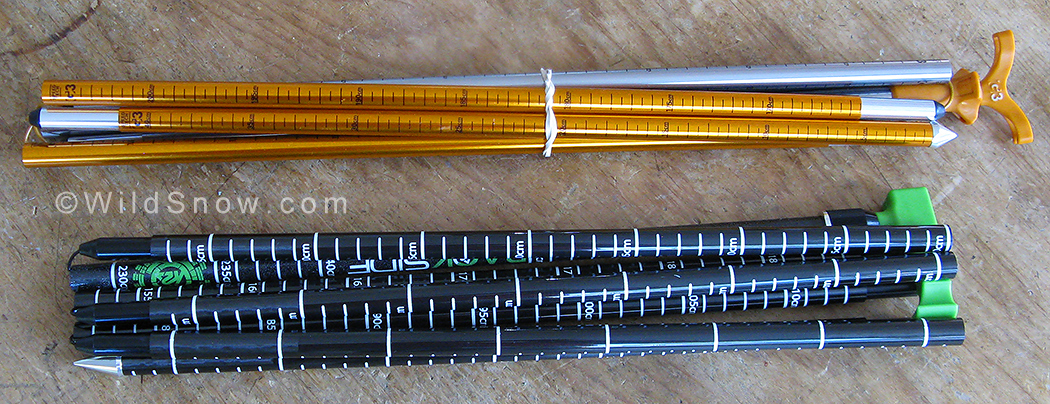

Make sure your probe is at least 240cm in length – additional features can be useful such as carbon material, longer, and distant measurements.

When looking at avalanche probes there are a few questions you can ask. Primarily, what snowpack am I skiing in. All probes should be either aluminum or carbon, there are pros and cons to both. Aluminum probes are heavier, but more durable to abrasion. A probe should be at least 240cm in length, and should have measurement marks in cm’s.

I prefer a longer probe (300+cm) in a maritime snowpack, and I look for a probe with measurements engraved in the probe rather than painted on as it tends to uphold its integrity over time. Do not get a probe less than 240cm or one that is plastic.

Touring specific, airbag packs and Avalungs

A pack to carry all of your kit for the day is obviously important. A specific backcountry pack is important and additional technologies such as airbags and Avalungs are something to think about. These tools are quickly becoming a standard part of a backcountry skiing kit, but they have their time and place.

First off, a backpack for touring should meet the following requirements: a shovel/probe specific pocket, and large enough to fit everything inside of it. It is not an adequate setup to have any of your safety equipment clipped or strapped to the outside of your pack.

Airbags are effective at reducing burial depth in wide open alpine terrain and can help to protect you from some associated trauma, but are not as effective in near and below treeline terrain. (See our airbag pack coverage.)

An Avalung is a tool to help extend the time someone can be buried before succumbing to asphyxiation, but require a narrow margin of correct use to be effective. Think about the type of backcountry touring you will be participating in, and that can help to guide you to the right tool for you.

This is a brief overview of the minimum standards of avalanche specific tools you should have in your kit when backcountry skiing. Of course, a focus on avalanche education will help you to avoid an avalanche incident. Your dedication to practicing rescue scenarios with these tools will maximize your ability to respond to an incident if it were to happen. There’s no replacement for this proactive approach to avalanche safety.

Support WildSnow. Shop for avalanche gear.

Jonathan Cooper (“Coop”) grew up in the Pacific Northwest and has been playing in the mountains since he was a teen. This was about the same time he made the fateful decision to strap a snowboard to his feet, which has led to a lifelong pursuit of powdery turns. Professionally speaking, he has been working as a ski guide, avalanche educator, and in emergency medicine for over a decade. During the winter months he can be found chasing snow, and passing on his passion for education and the backcountry through teaching avalanche courses for numerous providers in southwest Colorado, and the Pacific Northwest. Similarly, his passion for wilderness medicine has led him to teach for Desert Mountain Medicine all over the West. If you’re interested, you can find a course through Mountain Trip and Mountain West Rescue. In the end, all of this experience has merely been training for his contributions to the almighty WildSnow.com.