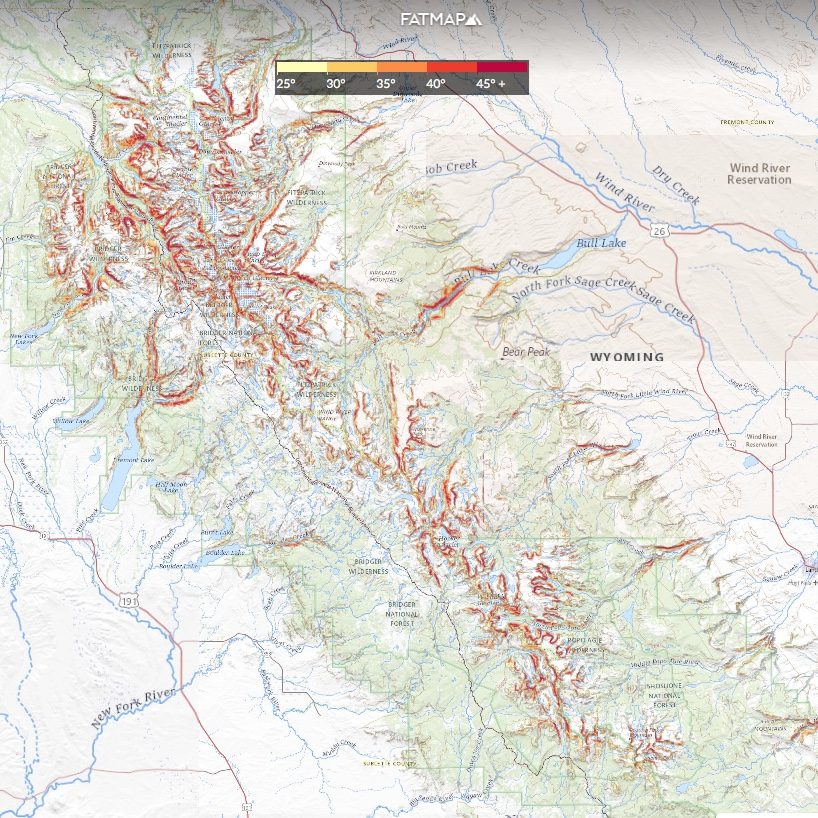

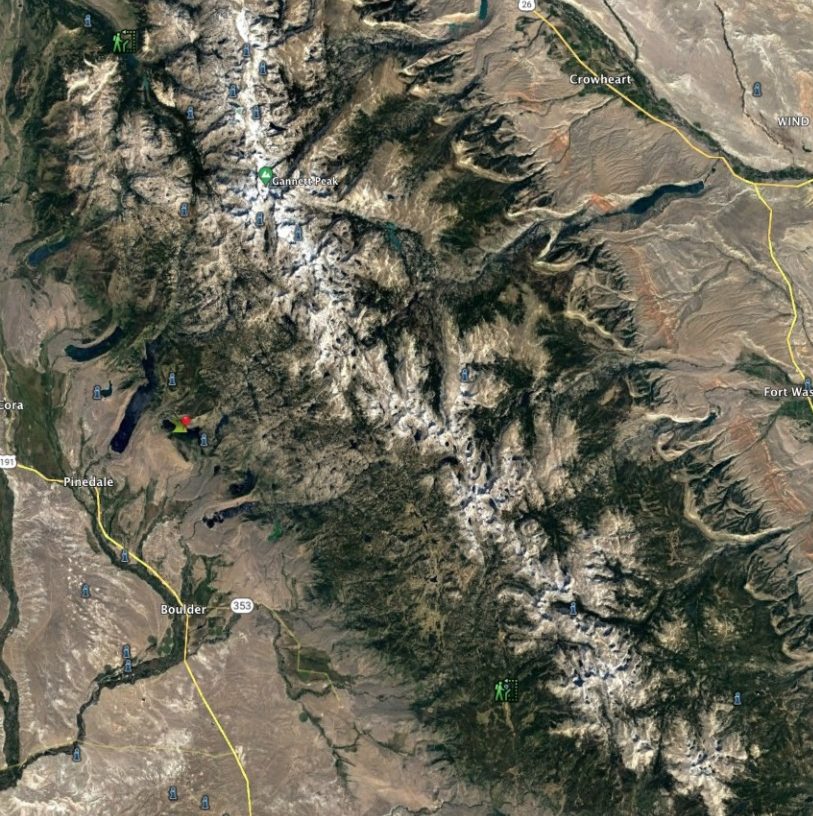

Big open Wyoming mountain country; a place where trip planning in a navigation app might come in handy. Photo: Brian Parker

I’m not exactly a late adopter, but I’m definitely not an early adopter. To the scorn of some, I was happy with my 88mm underfoot decade-old K2 Waybacks until I climbed and skied a Rainer classic with a fitter skier ascending on race-light gear. I pivoted soon after – building out a lighter but twitchier PDG setup. And it took until last year to be persuaded to break the 100mm underfoot threshold. There’s the context. I’ll opt for a technological advance after allowing the early adopters to charge ahead, take a step back, and charge again some more.

I’ve had versions of Gaia, Trailforks (pre-subscription), and FATMAP, and CalTopo on my phone since the onset of Covid. I rarely use any of them for pre-trip planning. However, on a massive plot of accessible private forest close to Bend, I often cross-referenced Trailforks and Gaia. Trailforks had data on established running and biking singletrack, whereas Gaia was a trove of pirate, but published, motorbike singletrack. I soon began “planning” my runs beforehand. It made sense; I was in relatively new terrain for me. I could generate a running circuit in Trailforks, and then export it into Gaia. There was no aimless running of note – just supreme empty-space link-ups that were easy to follow with the digital navigation assist.

Over the winter, a Lander-based friend and I planned a Wind River traverse on Google Earth. Route selection mistakes aside, the functionality of Google Earth was fine. In hindsight, a slope shading function would have been handy to help better predict at what time of day we would be navigating avy prone slopes. We were mainly concerned with warming temps in the afternoon as this was a mid-May trip.

We began to get shut down on the third of what we thought would be a four-day high-pressure window. Exclamation-point lightning strikes rattled us atop Bonney Pass. There, with about 20-foot visibility, flat light, snow-rain and thunder-booms, we hesitated where we shouldn’t have. Then we began scratching down on our skis.

Shortly after, I began thinking about using a navigation app as a planning and safety tool. But, by early September, I hadn’t made a move towards finding a solution.

The four main ski tour planning tools of note are FATMAP, CalTopo, Gaia, and onX. This piece will not be a treatise on the merits or flaws of these four tools. (We’ll get to that later in the season.) After asking around, it seems everyone has an opinion on what is most functional. My goal: find something that works best for me. And then, actually use it to plan ski tours. On this journey, I took a shortcut, and I’m glad I did.

I connected with David Mathes, a former Air Force Pararescueman based on the Idaho side of the Tetons. Mathes caught me at a low point – I had spent an excessive amount of time futzing with these tools but not hardwiring a procedure for using them to plan a tour. The opportunity cost was in play for me. It was a serendipitous moment; I needed direction. I chose not to wormhole on the Internet, finding tutorials on navigation apps specific to ski trip planning. Others may prefer that path; some good resources are out there.

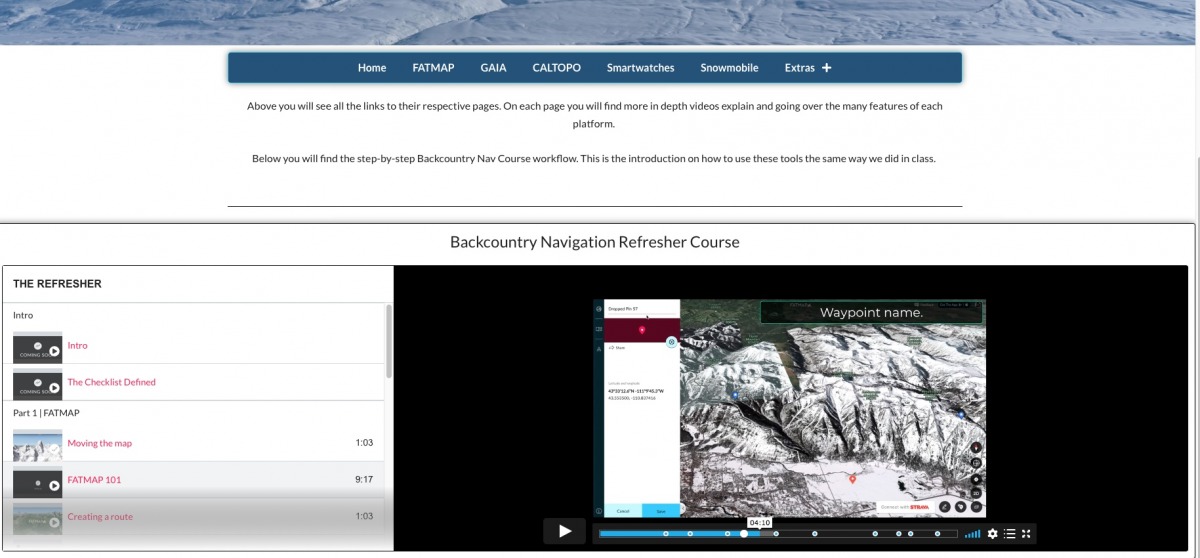

Mathes runs a startup called Backcountry Nav. He enrolled me in a three-hour zoom-based group class during which we would follow a checklist, most of which involved terrain selection, to plan an ascent and descent route. My class focused on FATMAP for the ascent and Gaia for the descent.

Mathes’ teaching methodology is linear, and he presents a concrete trip planning checklist/progression. The process includes basics like compass heading, terrain evaluation with a potential avalanche problem in mind, to details like what the plan might be if key landmarks are missed or the weather closes in. (I’m thinking of my Bonney Pass experience here.) And his approach to navigation planning is not burdensome: It’s a four-point checklist the user learns and then incorporates into their planned route. The ski plan for the day should be one you can articulate in a few minutes to your partners, and you get practice doing so during the class.

In the Backcountry Nav course, I worked through several class sections with the two other participants: an Alaska ski guide living in southern Oregon and a groomer and snowmobiler living 20 miles from Bend. Here’s the basic format of the class in terms of time management, Mathes repeated it for a session focusing on FATMAP and another on Gaia:

– Mathes presents the material.

– The group takes time for questions and answers with Mathes.

– Each student breaks into an independent virtual classroom to develop their route. The private classroom is time to practice in the navigation app. Mathes drops into the independent classroom a few times for one on one work. For me, this was key, as it helped me learn efficiencies within the app, and Mathes could direct me when I had neglected to include some aspects of the trip planning checklist.

-Finally, each student presents their plan to the group.

As a virtual teaching product, the independent breakout sessions were of high value. Yet, the masterstroke of the platform is the opportunity to present the trip plan. “To learn something, you must do something,” is a timeworn and effective teaching and learning strategy. Mathes uses this to good effect. Each student builds out a route and a plan, and then all participants present their plan using the checklist. So the “doing”, for example, happens twice within each navigation app.

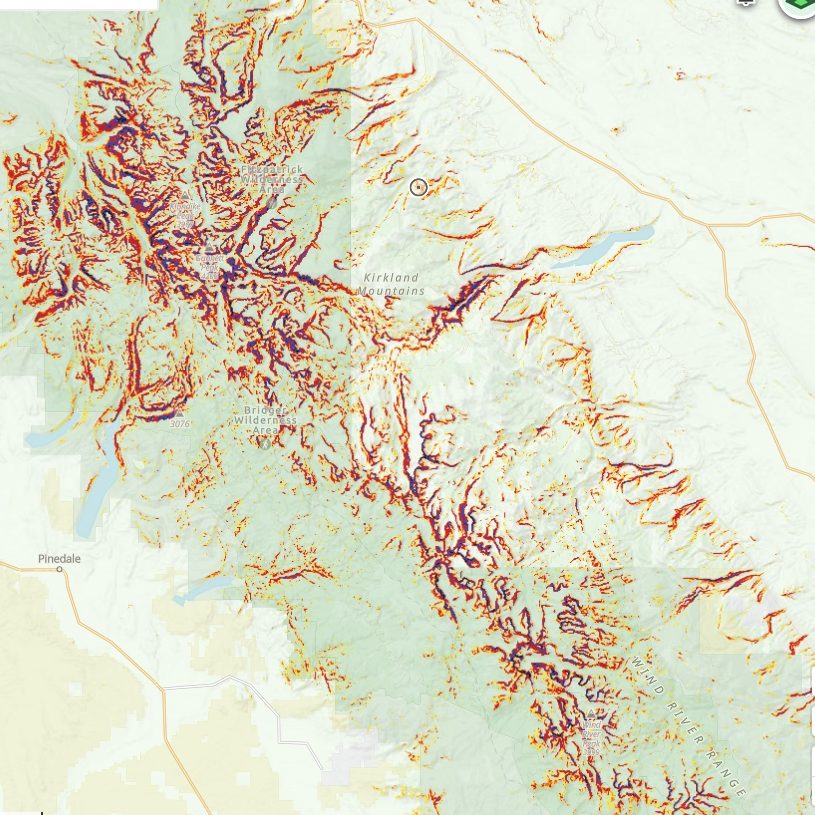

The class I took did not explore all things FATMAP or Gaia. However, we peeled back enough layers within each app to make them accessible and high functioning tools. And new to me was the ability to customize functions to provide a visual representation of the daily avalanche forecast and avalanche problem.

I can hear a segment of the online chorus singing this type of instruction is already available on Youtube. Aspects of that song are true, like how to connect waypoints and create a route. Or how to use angle shading to display slope angle – that’s presented in several how-to videos. Yet, the course, for me, provided structure and a usable and transferable checklist I could use to create my route. The required presentations by each student were also an opportunity for real-time feedback, practice, and reinforcement. It also sets students up to have a voice and speak to terrain selections in the future. I cannot overstate this point when thinking about the psychology of decision-making in a group. Although virtual, it felt as close to in-person learning as I have experienced in the past two years. The class embraces a welcome methodology that worked for me as a learner.

As a relative novice when planning in these apps, the pace was quick. I need practice. Mathes does ask that students enter the class having spent a nominal amount of time familiarizing themselves with each app’s essential functions. The Backcountry Nav site is built out with the requisite videos to go back and review. For example, there are videos titled FATMAP / GAIA 101, Drawing a route, Moving the maps, etc. The additional videos on the Backcountry Nav site include tutorials on Caltopo, Smartwatches, Snowmobiler-specific info, and several links to foster your navigation app savvy.

The group classes run with a minimum of two students and a max of four. Participants receive free 30-day access to Gaia and FATMAP and access to the review videos for a year after they take the class.

Pre-class, my honest assessment would peg me as an infrequent navigation app user unless planning something like a Wind River traverse. Now, I find myself already keying in on new terrain or longer traverses near home. As a potential ski day nears, I can go into my route files and customize functions for the daily avalanche forecast.

I see how this class is most fruitful for those coming in with some formal avalanche education. This course is meant to supplement formal avalanche instruction and the concepts you learn during those classes. The twist is, most of those concepts require having route planning and navigation skills. This course helps with any disconnect in understanding and reading the terrain, setting you up with the groundwork to safely plan a backcountry tour. The course is also not heavy on avalanche-geekspeak. But having some avalanche education allows for a more comprehensive learning outcome.

You’ll spend $60 on this three-hour class, which, again, includes a one-year access plan to all the additional video content. As I noted earlier, the opportunity cost of deep diving into this was a hurdle for me. Now, I’ve got my navigation app kickstart.

Jason Albert comes to WildSnow from Bend, Oregon. After growing up on the East Coast, he migrated from Montana to Colorado and settled in Oregon. Simple pleasures are quiet and long days touring. His gray hair might stem from his first Grand Traverse in 2000 when rented leather boots and 210cm skis were not the speed weapons he had hoped for. Jason survived the transition from free-heel kool-aid drinker to faster and lighter (think AT), and safer, are better.